GM -FBF –

Today, I want to share a story from the youth. At 10 years going to Washington,

D.C. to hear people talk about jobs and other things. Many of the people were

all right but the next speaker was a young preacher and he lit up the masses. I

askes who was he and I was told that he was going to lift our race up in a few

more years. Enjoy!

Remember – “We are tired. We are

tired of being beaten by policemen. We are tired of seeing our people locked up

in jail over and over again. And then you holler, ‘Be patient.’ How long can we

be patient? We want our freedom and we want it now.” – Rep. John Lewis, then

23-year-old chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

Today in our History = August

28,1963 – 100,000, blacks are at the mall in D.C. to listen to many people give

speaches.

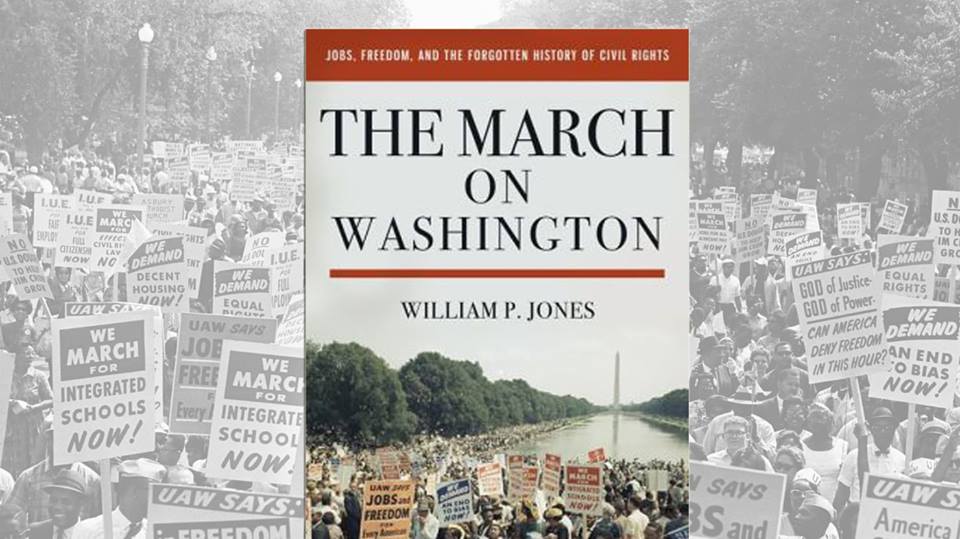

The March on Washington was a

massive protest march that occurred in August 1963, when some 250,000 people

gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. Also known as the

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the event aimed to draw attention to

continuing challenges and inequalities faced by African Americans a century

after emancipation. It was also the occasion of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s

now-iconic “I Have A Dream” speech.

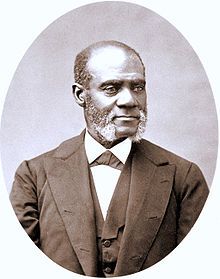

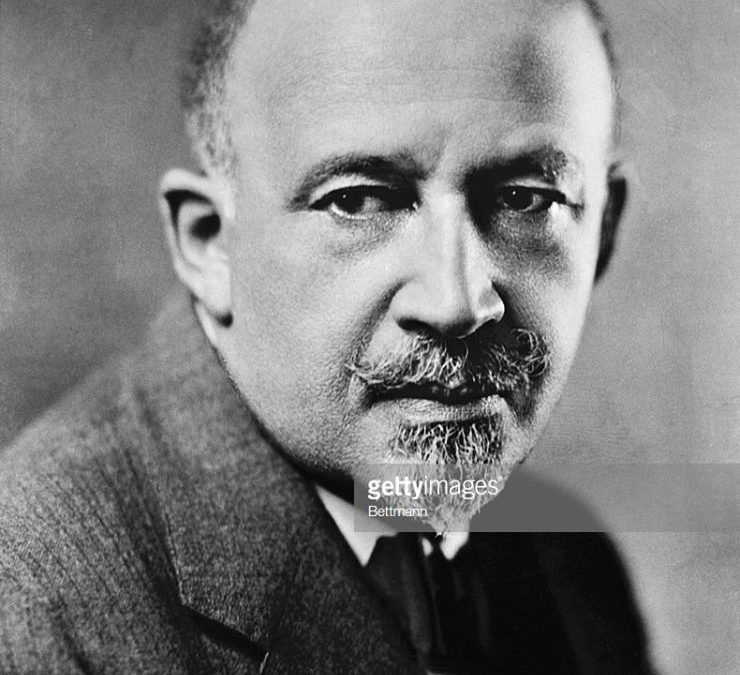

In 1941, A. Philip Randolph, head

of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and an elder statesman of the civil

rights movement, had planned a mass march on Washington to protest blacks’

exclusion from World War II defense jobs and New Deal programs.

But a day before the event,

President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with Randolph and agreed to issue an

executive order forbidding discrimination against workers in defense industries

and government and establishing the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC)

to investigate charges of racial discrimination. In return, Randolph called off

the planned march.

In the mid-1940s, Congress cut

off funding to the FEPC, and it dissolved in 1946; it would be another 20 years

before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) was formed to take on

some of the same issues.

Meanwhile, with the rise of the

charismatic young civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. in the mid-1950s,

Randolph proposed another mass march on Washington in 1957, hoping to

capitalize on King’s appeal and harness the organizing power of the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In May 1957, nearly 25,000

demonstrators gathered at the Lincoln Memorial to commemorate the third

anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education ruling, and urge the federal

government to follow through on its decision in the trial.

SCLC AND THE MARCH

In 1963, in the wake of violent attacks on civil rights demonstrators in

Birmingham, Alabama, momentum built for another mass protest on the nation’s

capital.

With Randolph planning a march

for jobs, and King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

planning one for freedom, the two groups decided to merge their efforts into

one mass protest.

That spring, Randolph and his

chief aide, Bayard Rustin, planned a march that would call for fair treatment

and equal opportunity for black Americans, as well as advocate for passage of

the Civil Rights Act (then stalled in Congress).

President John F. Kennedy met

with civil rights leaders before the march, voicing his fears that the event

would end in violence. In the meeting on June 22, Kennedy told the organizers

that the march was perhaps “ill-timed,” as “We want success in the Congress,

not just a big show at the Capitol.”

Randolph, King and the other leaders

insisted the march should go forward, with King telling the president:

“Frankly, I have never engaged in any direct-action movement which did not seem

ill-timed.”

JFK ended up reluctantly

endorsing the March on Washington, but tasked his brother and attorney general,

Robert F. Kennedy, with coordinating with the organizers to ensure all security

precautions were taken. In addition, the civil rights leaders decided to end

the march at the Lincoln Memorial instead of the Capitol, so as not to make members

of Congress feel as if they were under siege.

WHO WAS AT THE MARCH ON

WASHINGTON?

Officially called the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the historic

gathering took place on August 28, 1963. Some 250,000 people gathered at the

Lincoln Memorial, and more than 3,000 members of the press covered the event.

Fittingly, Randolph led off the

day’s diverse array of speakers, closing his speech with the promise that “We

here today are only the first wave. When we leave, it will be to carry the

civil rights revolution home with us into every nook and cranny of the land,

and we shall return again and again to Washington in ever growing numbers until

total freedom is ours.”

Other speakers followed,

including Rustin, NAACP president Roy Wilkins, John Lewis of the Student

Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), civil rights veteran Daisy Lee Bates

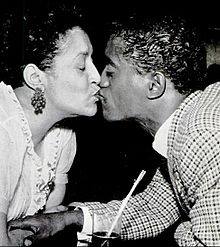

and actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee. The march also featured musical

performances from the likes of Marian Anderson, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan and

Mahalia Jackson.

“I HAVE A DREAM” SPEECH

King agreed to speak last, as all the other presenters wanted to speak earlier,

figuring news crews would head out by mid-afternoon. Though his speech was

scheduled to be four minutes long, he ended up speaking for 16 minutes, in what

would become one of the most famous orations of the civil rights movement—and

of human history.

Though it has become known as the

“I Have a Dream” speech, the famous line wasn’t actually part of King’s planned

remarks that day. After leading into King’s speech with the classic spiritual

“I’ve Been ‘Buked, and I’ve Been Scorned,” gospel star Mahalia Jackson stood

behind the civil rights leader on the podium.

At one point during his speech,

she called out to him, “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin, tell ‘em about the

dream!” referring to a familiar theme he had referenced in earlier speeches.

Departing from his prepared

notes, King then launched into the most famous part of his speech that day:

“And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still

have a dream.” From there, he built to his dramatic ending, in which he

announced the tolling of the bells of freedom from one end of the country to

the other.

“And when this

happens…we will be able to speed up that day when all God’s children, black men

and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to

join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last!

Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’” Research more about

this march for jobs and how we as a people endored, SARE WITH YOUR BABIES AND

MAKE IT A CHAMPION DAY!