Author: Champion One

August 14 1894- Ada Beatrice Queen Victoria

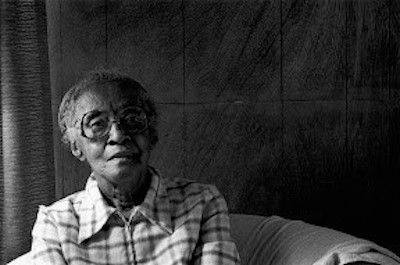

GM – FBF – Today, I have a story that I know you have not heard of. This lady was a diva long before any woman singer/dancer or artist that you can think of. She was strong willed and lived a long life. Enjoy the story of “Bricktop”!

Remember – ” As I get older in life, I hear talk about this new great female singer or artist and I love them and the work that they do but for some reason America has forgotten about me. – Ada ” Bricktop” Smith

Today in our History – August 14, 1894 – Ada Beatrice Queen

Victoria Louise Virginia Smith, better known as Bricktop, was

born.

Ada Beatrice Queen Victoria Louise Virginia Smith, better known as Bricktop, (August 14, 1894 – February 1, 1984) was an American dancer, jazz singer, vaudevillian, and self-described saloon-keeper who owned the nightclub Chez Bricktop in Paris from 1924 to 1961, as well as clubs in Mexico City and Rome. She has been called “…one of the most legendary and enduring figures of twentieth-century American cultural history.”

Smith was born in Alderson, West Virginia, the youngest of four children by an Irish father and a black mother. When her father died, her family relocated to Chicago. It was there that saloon life caught her fancy, and where she acquired her nickname, “Bricktop,” for the flaming red hair and freckles inherited from her father. She began performing when she was very young, and by 16, she was touring with TOBA (Theatre Owners’ Booking Association) and on the Pantagesvaudeville circuit. Aged 20, her performance tours brought her to New York City. While at Barron’s Exclusive Club, a nightspot in Harlem, she put in a good word for a band called Elmer Snowden’s Washingtonians, and the club booked them. One of its members was Duke Ellington.

Her first meeting with Cole Porter is related in her obituary in

the Huntington (West Virginia) Herald-Dispatch:

Porter once walked into the cabaret and ordered a bottle of wine. “Little

girl, can you do the Charleston?” he asked. Yes, she said. And when she

demonstrated the new dance, he exclaimed, “What legs! What legs!”

John Steinbeck was once thrown out of her club for “ungentlemanly behavior.” He regained her affection by sending a taxi full of roses.

By 1924, she was in Paris. Cole Porter hosted many parties, “lovely parties” as Bricktop called them, where he hired her as an entertainer, often to teach his guests the latest dance craze such as the Charleston and the Black Bottom. In Paris, Bricktop began operating the clubs where she performed, including The Music Box and Le Grand Duc. She called her next club “Chez Bricktop,” and in 1929 she relocated it to 66 rue Pigalle. Her headliner was a young Mabel Mercer, who was to become a legend in cabaret.

Known for her signature cigars, the “doyenne of cafe

society” drew many celebrated figures to her club, including Cole Porter,

the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald mentions

the club in his 1931 short story Babylon Revisited. Her protégés included Duke

Ellington, Mabel Mercer and Josephine Baker. She worked with Langston Hughes

when he was still a busboy. The Cole Porter song “Miss Otis Regrets”

was written especially for her to perform.[citation needed] Django Reinhardt

and Stephane Grappelli wrote a song called “Brick Top,” which they

recorded in Paris in 1937 and in Rome in 1949.

She married saxophonist Peter DuConge in 1929.

Though they separated after a few years, they never divorced, Bricktop later saying that “as a Catholic I do not recognize divorce”. According to Jean-Claude Baker, one of Josephine Baker’s children, as recorded in his book about his mother’s life, titled Josephine: The Hungry Heart, Baker and Bricktop were involved in a lesbian affair for a time, early in their careers.

Bricktop broadcast a radio program in Paris from 1938 to 1939, for the French government. During WWII, she closed “Chez Bricktop” and moved to Mexico City where she opened a new nightclub in 1944. In 1949, she returned to Europe and started a club in Rome. Bricktop closed her club and retired in 1961 at the age of 67, saying: “I’m tired, honey. Tired of staying up all night.” Afterwards, she moved back to the United States.

Bricktop continued to perform as a cabaret entertainer well into her eighties, including some engagements at the age of 84 in London, where she proved herself to be as professional and feisty as she had ever been and included Cole Porter’s “Love for Sale” in her repertoire.

Bricktop made a brief cameo appearance, as herself, in Woody Allen’s 1983 mockumentary film Zelig, in which she “reminisced” about a visit by Leonard Zelig to her club, and an unsuccessful attempt by Cole Porter to find a rhyme for “You’re the tops, you’re Leonard Zelig.” She appeared in the 1974 Jack Jordan’s film Honeybaby, Honeybaby, in which she played herself, operating a “Bricktop’s” in Beirut, Lebanon.

In 1972, Bricktop made her only recording, “So Long Baby,” with Cy Coleman. Nevertheless, she also recorded a few Cole Porter songs in New-York City at the end of the seventies with pianist Dorothy Donegan. The session was directed by Otis Blackwell, produced by Jack Jordan on behalf of the Sweet Box Company. The songs recorded are: “Love For Sale”, “Miss Otis Regrets”, “Happiness Is a Thing Called Joe”, “A Good Man Is Hard To Find”, “Am I Blue?” and “He’s Funny That Way”. This recording was never released as of today. She preferred not to be called a singer or dancer, but rather a performer.

She wrote her autobiography, Bricktop by Bricktop, with the help of James Haskins, the prolific author who wrote biographies of Thurgood Marshall and Rosa Parks. It was published in 1983 by Welcome Rain Publishers (ISBN 0-689-11349-8). Bricktop died in her sleep in her apartment in Manhattan in 1984, aged 89. She remained active into her old age and according to James Haskins, had talked to friends on the phone hours before her death. She is interred in the Zinnia Plot (Range 32, Grave 74) at Woodlawn Cemetery. Reed more about this great American and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

August 13 1906

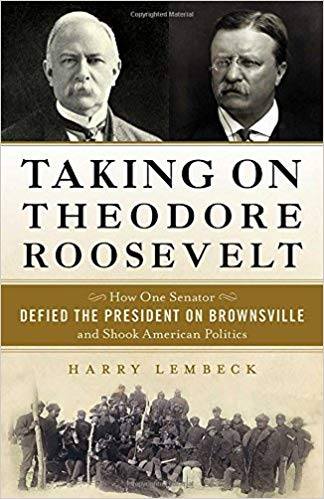

GM – FBF – Today I would like to share with you a story that was so bad, the President hurt many people of color and their families. It would be know as the Brownsville Case. Enjoy!

Remember – ” I lost my livelthood and my future because of a lie! – Black Solder

Today in our History – August 13, 1906 – Black soldiers accused of killing a white bartender and a Hispanic police officer was wounded by gunshots in the town.

Since arriving at Fort Brown on July 28, 1906, the black US

soldiers had been required to follow the legal color line mandate from white

citizens of Brownsville, which included the state’s racial segregation law

dictating separate accommodation for black people and white people, and Jim

Crow customs such as showing respect for white people, as well as respect for

local laws.

]

A reported attack on a white woman during the night of August 12 so incensed

many townspeople that Maj. Charles W. Penrose, after consultation with Mayor

Frederick Combe, declared an early curfew for soldiers the following day to

avoid trouble.

On the night of August 13, 1906, a white bartender was killed

and a Hispanic police officer was wounded by gunshots in the town. Immediately

the residents of Brownsville cast the blame on the black soldiers of the 25th

Infantry at Fort Brown. But the all-white commanders at Fort Brown confirmed

that all of the soldiers were in their barracks at the time of the shootings.

Local whites, including Brownsville’s mayor, still claimed that some of the

black soldiers participated in the shooting.

Local townspeople of Brownsville began providing evidence of the 25th

Infantry’s part in the shooting by producing spent bullet cartridges from Army

rifles which they said belonged to the 25th’s men. Despite the contradictory

evidence that demonstrated the spent shells were planted in order to frame men

of the 25th Infantry in the shootings, investigators accepted the statements of

the local whites and the Brownsville mayor.

When soldiers of the 25th Infantry were pressured to name who fired the shots, they insisted that they had no idea who had committed the crime. Captain Bill McDonald of the Texas Rangers investigated 12 enlisted men and tried to tie the case to them. The local county court did not return any indictments based on his investigation, but residents kept up complaints about the black soldiers of the 25th.

At the recommendation of the Army’s Inspector General, President Theodore Roosevelt ordered 167 of the black troops to be dishonorably discharged because of their “conspiracy of silence”. Although some accounts have claimed that six of the troops were Medal of Honor recipients, historian Frank N. Schubert has shown that none was. Fourteen of the men were later reinstated into the army. The dishonorable discharge prevented the 153 other men from ever working in a military or civil service capacity. Some of the black soldiers had been in the U.S. Army for more than 20 years, while others were extremely close to retirement with pensions, which they lost as a result.

The prominent African-American educator and activist, Booker T. Washington, president of Tuskegee Institute, got involved in the case. He asked President Roosevelt to reconsider his decision in the affair. Roosevelt dismissed Washington’s plea and allowed his decision to stand.

Both blacks and many whites across the United States were outraged at Roosevelt’s actions. The black community began to turn against him, although it had previously supported the Republican president (in addition to maintaining loyalty to the party of Abraham Lincoln, black people approved of Roosevelt having invited Booker T. Washington to dinner at the White House and speaking out publicly against lynching). The administration withheld news of the dishonorable discharge of the soldiers until after the 1906 Congressional elections, so that the pro-Republican black vote would not be affected. The case became a political football, with William Howard Taft, positioning for the next candidacy for presidency, trying to avoid trouble.

Leaders of major black organizations, such as the Constitution League, the National Association of Colored Women, and the Niagara Movement, tried to persuade the administration not to discharge the soldiers, but were unsuccessful. From 1907–1908, the US Senate Military Affairs Committee investigated the Brownsville Affair, and the majority in March 1908 reached the same conclusion as Roosevelt. Senator Joseph B. Foraker of Ohio had lobbied for the investigation and filed a minority report in support of the soldiers’ innocence. Another minority report by four Republicans concluded that the evidence was too inconclusive to support the discharges. In September 1908, prominent educator and leader W. E. B. DuBois urged black people to register to vote and to remember their treatment by the Republican administration when it was time to vote for president.

Feelings across the nation remained high against the government actions, but with Taft succeeding Roosevelt as President, and Foraker failing to win re-election, some of the political pressure declined.

On February 23, 1909, the Committee on Military Affairs recommended favorably on Bill S.5729 for correction of records and reenlistment of officers and men of Companies B, C, and D of the 25th Infantry.

Senator Foraker was not re-elected. He continued to work on the Brownsville affair during his remaining time in office, guiding a resolution through Congress to establish a board of inquiry with the power to reinstate the soldiers. The bill, which the administration did not oppose, was less than Foraker wanted. He had hoped for a requirement that unless specific evidence was shown against a man, he would be allowed to re-enlist. The legislation passed both houses, and was signed by Roosevelt on March 2, 1909.

On March 6, 1909, shortly after he left the Senate, Foraker was the guest of honor at a mass meeting at Washington’s Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church. Though both whites and African Americans assembled to recognize the former senator, all the speakers but Foraker were African American. Presented with a silver loving cup, he addressed the crowd,

I have said that I do not believe that a man in that battalion had anything to do with the shooting up of “Brownsville,” but whether any one of them had, it was our duty to ourselves as a great, strong, and powerful nation to give every man a hearing, to deal fairly and squarely with every man; to see to it that justice was done to him; that he should be heard.

On April 7, 1909, under the provisions of the Act of March 30, 1909, a Military Court of Inquiry was set up by Secretary of War Jacob M. Dickinson to report on the charges and recommend for reenlistment those men who had been discharged under Special Order # 266, November 9, 1906. Of the 167 discharged men, 76 were located as witnesses, and 6 did not wish to appear.

The 1910 Court of Military Inquiry undertook an examination of

the soldiers’ bids for re-enlistment, in view of the Senate committee’s

reports, but its members interviewed only about one-half of the soldiers

discharged. It accepted 14 for re-enlistment, and eleven of these re-entered

the Army.[4][10]

The government did not re-examine the case until the early 1970s.

In 1970, historian John D. Weaver published The Brownsville Raid, which investigated the affair in depth. Weaver argued that the accused members of the 25th Infantry were innocent and that they were discharged without benefit of due process of law as guaranteed by the United States Constitution. After reading his book, Congressman Augustus F. Hawkins of Los Angeles introduced a bill to have the Defense Department re-investigate the matter to provide justice to the accused soldiers.

In 1972, the Army found the accused members of the 25th Infantry to be innocent. At its recommendations, President Richard Nixon pardoned the men and awarded them honorable discharges, without backpay. These discharges were generally issued posthumously, as there were only two surviving soldiers from the affair: one had re-enlisted in 1910. In 1973, Hawkins and Senator Hubert Humphreygained congressional passage of a tax-free pension for the last survivor, Dorsie Willis, who received $25,000. He was honored in ceremonies in Washington, DC, and Los Angeles. Research more about the case and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

August 12 1880- George Jordan

GM – FBF – Today, I want to share with you one of the brave Black Men who represented us as a Buffalo Soldier after the Civil War and Reconstruction. The time that the Country was completing the extermination of the Native Americans or as it was called “The Indian Wars”. Even though the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution; known collectively as the Civil War Amendments were passed, the Black race in America was still considered to be second class citizens in many parts of the country as the “ERA OF JIM CROW” had begun. So let’s have the black man get rid of the red man.

Even our American History supports the strong efforts of the contributions and heroism of the Buffalo Soldiers by 1890, the state of Louisiana passed the Separate Car Act, which required separate accommodations for blacks and whites on railroads, including separate railway cars. This would be heard by the Supreme Court in 1896 and Plessy v. Ferguson, will be the law of the land until the 1960’s. Teach yourself and your babies our part of this American History. Remember and enjoy!

Remember – “The earth and the horse moved as it should be and the warrior that the blue coats send to defeat us we respect as our God – (Wakan Tanka – The Great Spirit) asked us too. I have no Battle with the Buffalo Soldier” – Sitting Bull – Hunk papa Lakota holy man & leader

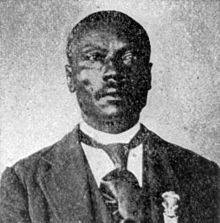

Today in our History – August 12, 1880 – George Jordan was awarded the Medal of Honor for gallantry in battle at Fort Tularosa, New Mexico.

George Jordan, buffalo soldier and Medal of Honor recipient, hailed from rural Williamson County in central Tennessee. Enlisting in the 38th Infantry Regiment on 25 December 1866, the short and illiterate Jordan proved a good soldier. In January 1870, he transferred to the 9th Cavalry’s K Troop, his home for the next twenty-six years. Earning the trust of his troop commander, Captain Charles Parker, Jordan was promoted to corporal in 1874; by 1879, he wore the chevrons of a sergeant. It was during these years that Jordan learned how to read and write, an accomplishment that certainly facilitated his advancement in the Army.

On 14 May 1880, following a difficult forced march at night, a twenty-five man detachment under Jordan successfully repulsed a determined attack on old Fort Tularosa, New Mexico, by more numerous Apaches. The next year on 12 August, still campaigning against the Apaches, Jordan’s actions contributed to the survival of a detachment under Captain Parker when they were ambushed in Carrizo Canyon, New Mexico. Although neither engagement received much attention initially, in 1890 Jordan was awarded a Medal of Honor for Tularosa and a Certificate of Merit for Carrizo Canyon.

By the time of his retirement in 1896 at Fort Robinson, Jordan had served ten years as first sergeant of a veteran troop renowned for its performance against the Apache and Sioux. Jordan joined other buffalo soldier veterans in nearby Crawford, Nebraska, and became a successful land owner, although his efforts to vote bore little fruit.

Jordan’s health declined dramatically in the autumn of 1904 but Jordan was denied admission to the Fort Robinson’s hospital. Told to try the Soldiers’ Home in Washington, D.C., he died 19 October, the post chaplain officially complaining that Jordan “died for the want of proper attention.” Jordan was buried in the Fort Robinson cemetery, his funeral conducted with full honors and attended by most of the post’s personnel, a bittersweet ending to the story of an exemplary buffalo soldier. Research more about these great Americans and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

August 11 1872- Soloman Carter Fuller

GM – FBF – Today I want to share with you the story of the first Black psychiatrist. He also was at the forefront of understanding the effects of Alzheimer’s, a disease which I have lost some family members and parents of some of my friends. When people tell you that our race is just about entertainment and sports let them know that we have a rich background in all fields of the human race. Enjoy!

Remember – “When you know that you don’t know, you’ve got to read.” Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller

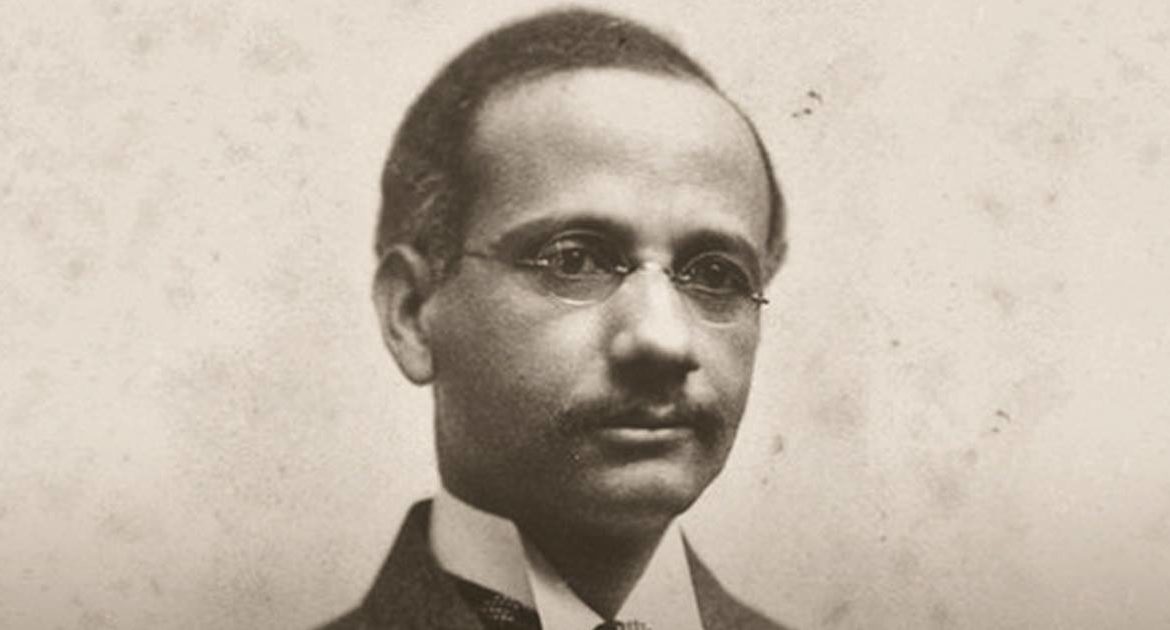

Today in our History – August 11, 1872 – Solomon Carter Fuller was born.

Solomon Carter Fuller, an early 20th century psychiatrist, researcher, and medical educator, was born on August 11, 1872 in Monrovia, Liberia. His parents, Solomon C. and Anna Ursilla (James) Fuller, were Americo-Liberians. Solomon Carter Fuller was the first African American psychiatrist. He also performed considerable research concerning degenerative diseases of the brain. Solomon’s grandfather was a Virginia slave who bought his and his wife’s freedom and moved to Norfolk, Virginia. The grandfather then emigrated to Liberia in 1852 to help establish a settlement of African Americans.

Fuller always showed an interest in medicine, especially since his grandparents were medical missionaries in Liberia. In 1889, Solomon migrated to the United States to attend Livingstone College in Salisbury, North Carolina. He then attended Long Island College Medical School and completed his medical degree at the Boston University School of Medicine in 1897. Fuller completed an internship at Westborough State Hospital in Boston and stayed on as a pathologist. He eventually became a faculty member of the Boston University School of Medicine. In 1909 Fuller married Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, an internationally known sculptor. The couple had three children, Solomon C., William T., and Perry J. Fuller.

Fuller faced discrimination in the medical field in the form of unequal salaries and underemployment. His duties often involved performing autopsies, an unusual procedure for that era. While performing these autopsies Fuller made discoveries which allowed him to advance in his career as well contribute to the scientific and medical communities.

Solomon Fuller’s major contribution was to the growing clinical knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease. As part of his post-graduate studies at the University of Munich (Germany), Fuller researched pathology and specifically neuropathology. In 1903 Solomon Carter Fuller was one of the five foreign students chosen by Alois Alzheimer to do research at the Royal Psychiatric Hospital at the University of Munich. He also helped correctly diagnose and train others to correctly diagnose the side effects of syphilis to prevent black war veterans from getting misdiagnosed, discharged, and ineligible for military benefits. He trained these young doctors at the Veteran’s Hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama before the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments (1932-1972).

Through much of his early professional career (1899-1933) Fuller was employed with Boston University’s School of Medicine where the highest position he attained was associate professor. Solomon Carter Fuller died of diabetes in 1953 in Framingham, Massachusetts. In 1974, the Black Psychiatrists of America created the Solomon Carter Fuller Program for young black aspiring psychiatrists to complete their residency. The Solomon Carter Fuller Mental Health Center in Boston is also named after Dr. Fuller. Research more about blacks in the medical profession and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

August 10 1965- Cassandra Quin Butt

GM – FBF – Today, I would like to share with you the story of a young lady who was with President Obama from his early days in IL. throught his time in the White House, Enjoy!

Remember – ” Dreams are just thant unless you work on

turning a dream into your reality” –

Cassandra Quin Butt

Today in our History – August 10, 1965 – Deputy White House Counsel to President Barack Obama is born.

Cassandra Quin Butt is Deputy White House Counsel to President Barack Obama on issues relating to civil rights, domestic policy, healthcare, and education. She brought seventeen years of experience in politics and policy to her position. She is a long-time friend of the President, acting as an advisor during his term in the U.S. Senate and throughout his presidential campaign. Additionally, she served as a member of the presidential transition team.

Butts was born on August 10, 1965, in Brooklyn, New York, and at age nine moved to Durham, North Carolina. She graduated from the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill with a BA in political science. While at UNC she participated in anti-apartheid protests. She entered Harvard Law School in 1988 where her friendship with future President Barack Obama began when both were filling out forms in the student financial aid line. Butts continued her activism at Harvard where she joined in protests regarding hiring practices for faculty of color. She received a JD from Harvard in 1991.

The first black woman to function as Deputy White House Counsel gradually rose to prominence Her first job was as a counselor at the YMCA in Durham, North Carolina, and after graduating from UNC she worked for a year as a researcher with the African News Service in Durham. For six years she was a registered lobbyist with the Center for American Progress (CAP), rising to Senior Vice President.

Butts served as an election observer in the 2000 Zimbabwean parliamentary elections and was a counsel to Senator Harris Wofford of Pennsylvania. Butts then performed litigation and policy work as assistant counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., where she worked on civil rights policy and litigated voting rights and school desegregation cases. She spent seven years working as a senior advisor to U.S. Congressman and Democratic Majority Leader Dick Gephardt of Missouri. Working with Gephardt honed her political skills with her appointment as policy director on his 2004 presidential campaign, during which she helped formulate a universal health care plan. She also was his principal advisor on matters involving judiciary, financial services, and information technology issues. By 1998 Butts provided strategic advice to the Majority Leader on a range of issues including the 1998 presidential impeachment and legislation relating to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. While working for Gephardt she helped draft the groundbreaking September 11th Victim Compensation Fund of 2001.

In her current White House position, Butts advises President Obama on general domestic policy concerns. Additionally, she specializes in matters related to presidential policy, ethical questions, financial disclosures, and legal issues surrounding the President’s decision to sign or veto legislation. Research more about this great American and share with your babies. Make it A champion day!

August 9 1902- Mary Lucille Perkins

GM – FBF – And what a great day it will be. I would like to share a story with you. How many of you have had someone knock on your door not to buy anything but wants to sit and visit with you about their vision spin? Sometimes you hide and won’t answer the door. Today let’s look at a member of that relious group. Enjoy!

Remember – ” Many blacks will one day see the Importance of joining our family” – Mary Lucille Perkins Bankhead,

Today in our History – August 9, 1902 – Mary Lucille Perkins Bankhead dies.

Mary Lucille Perkins Bankhead, lifelong resident of Salt Lake City and member of the Genesis Group leadership, was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, on August 9, 1902. Her father, Sylvester Perkins, was a cowboy and farmer. Her mother, Martha Anne Jane Stevens Perkins Howell, was a homemaker and a farmworker. Martha and Sylvester celebrated a double wedding in 1899 with Nettie Jane (granddaughter of the famous Jane Manning James) and Louis Leggroan. The Perkins family proudly claimed Green Flake (Martha’s grandfather and one of three “colored servants” among the vanguard Mormon pioneers) as their ancestor.

Lucille Perkins grew up on a homestead originally granted by President Ulysses S. Grant. She was a lifelong member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). According to Bankhead, the relationship among neighbors was characterized more by camaraderie than by racial tensions, though she certainly found racial tension in her LDS congregation.

In 1922 Lucille Perkins married Thomas LeRoy Bankhead, a descendant of Nathan Bankhead, a slave of Mormon pioneers. Lucille and LeRoy had a total of eight children. The marriage lasted forty-five years until LeRoy died on February 18, 1968.

Bankhead maintained a close but complicated relationship with the LDS Church throughout her life. Her father and husband were Mormons, but both had refused to attend church. Her husband participated in social engagements and charitable activities sponsored by the church and accompanied Bankhead to meetings. However, rather than attend these meetings, he would wait for Lucille in the car in cold weather or in storms.

Their sons were practicing Mormons, but during their youth, the LDS Church was still enforcing its ban on blacks entering the priesthood. The Bankhead sons did not remain active in the LDS Church. Lucille Bankhead believed that people, rather than God, were responsible for the priesthood restriction.

Bankhead challenged the legitimacy of white supremacy on several fronts. In 1939 a Utah state senator proposed to relocate Salt Lake City’s black residents to a different side of the city in an effort to obtain black-owned real estate. Bankhead and members of her arts and crafts club went to the capitol and sat in the gallery for several hours. She and her group were able to stop this land repossession. When Bankhead served as secretary for the Daughters of Utah Pioneers, she was set to deliver a speech. As she approached the entrance of the meeting hall, the doorman closed the door. He expected Bankhead to enter through the kitchen, but she managed to have the door opened for her and delivered her speech as planned.

When the Genesis Group (a support group for black Mormons) was organized in 1971, Lucille Bankhead became the president of its Relief Society (the women’s organization). She also participated in the proxy endowment (an LDS temple ordinance) of Jane Elizabeth Manning James, a black woman close to LDS founder Joseph Smith. She was also a featured speaker at the first annual Ebony Rose Black History conference in 1987.

Mary Lucille Perkins Bankhead passed away in Salt Lake City on June 16, 1994, and is buried in the Elysian Gardens Cemetery. She was ninety-one. Research more about this great American and share withh your babies. Make it a champion day!

August 8 1989

GM –FBF – Today, I want to share a story with you, it begins with me being the advisor to the SGA at Junior High School Number 3 in Trenton, N.J. and I along with other students, facility, parents/guardians and citizens of Trenton listening to our Governor Tom Kean deliver the commencement address.

THE FIRST TIME A SITTING GOVERNOR gave a commencement address to a Trenton, N.J. school. I was awarded “Teacher of the year” for Mercer County but I was also (RIF)’ed reduction of force from the Trenton School System. I was blessed that Ewing High School took me in as a History teacher and Football and Track coach. I also was advisor to my own club that I had formed while in Trenton called – The Spectrum Project.

When I had heard that Congressman Leland had died, I called my friend Rep. Donald Payne (D-NJ) who was a member of the Congressional Black Congress and asked if my club could have the rights to Mr. Leland and give awards under his lasting efforts. My students representing 6 different school districts in Mercer County, NJ went to honor “Mickey” in his home 5th Ward Texas at Phillis Whitely High School. I was proud of my students because the Governor of Texas – Ann Richards, Mayor of Houston – Kathryn J. Whitmire and Barbara Jordan – who represented Texas Southern University were there to also honor Congressman Leland. Shawn (Harris) Mitchell was one of the speakers that day and she works this day at Trenton’s Board of Education and ask her what she felt about being a member of the Spectrum Project. Enjoy “Mickey’s” story!

Remember – “In a world that has so many challenges, being fed a good meal should not be one of the challenges” – George Thomas “Mickey” Leland,

Today in our History – August 8, 1989 – George Thomas “Mickey” Leland III dies.

“Mickey” was America’s most effective spokesman for hungry people in the United States and throughout the world. During six terms in the Congress, six years as a Texas state legislator and, Democratic National Committee official, he focused much needed attention on issues of health and hunger and rallied support that resulted in both public and private action. Leland combined the skills of the charismatic leader with the power of a sophisticated behind-the-scenes congressman. He matured during his years in Congress into a brilliantly effective and influential advocate for food security and health care rights for every human being. When Mickey Leland died in 1989, he was Chairman of the House Select Committee on Hunger. His committee studied the problems associated with domestic and international hunger and then delivered the practical solution of food.

George Thomas “Mickey” Leland, III, was born on November 27, 1944, in Lubbock, Texas, to Alice and George Thomas Leland, II. At an early age, he, along with his mother and brother (William Gaston Leland), took up residence in the Fifth Ward of Houston, Texas.

During the administration of President Leonard O. Spearman, Leland received an honorary doctorate degree from Texas Southern University. He married the former Alison Clark Walton, a Georgetown University law student, in 1983. Congressman Leland fathered three children, Jarrett David (born February 6, 1986) and twins, Austin Mickey and Cameron George (born January 14, 1990, after Leland’s death).

Congressman Leland was elected in November 1978 to the United States House of Representatives from the 18th Congressional District of Houston, Texas. His Congressional district included the neighborhood where he had grown up, and he was recognized as a knowledgeable advocate for health, children and the elderly. His leadership abilities were quickly noted in Washington, and he was chosen Freshman Majority Whip in his first term, and later served twice as At-Large Majority Whip. Leland was re-elected to each succeeding Congress until his death in August 1989.

Mickey Leland’s sincere concern for ethnic equality earned him a leadership position in politics. During 1985-86, Congressman Leland served as Chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) for the 99th Congress. The CBC was created in 1971 with only 13 members. By 1987, the CBC had grown to 23 members. Leland was also a member of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) from 1976-85. He served as Chairman of the DNC’s Black Caucus from 1981-1985, and in that capacity, he served on the DNC’s Executive Committee.

When running for re-election in 1988, Congressman Leland was quoted as saying, “This is my 10th year in Congress, and I want to go back.” He stated further, “The more influence I get, the more I can help the people of the 18th District, but also (people) throughout the country.” Leland was becoming increasingly successful in international human rights and world hunger issues. He fought against the injustice of South African Apartheid, and led successful boycotts against South Africa Airways and was instrumental in obtaining a congressional override of President Reagan’s veto of economic sanctions against South Africa.

Mickey

Leland died as he had lived, on a mission seeking to help those most in need.

While leading another relief mission in 1989, to an isolated refugee camp,

Fugnido, in Ethiopia, which sheltered thousands of unaccompanied children

fleeing the civil conflict in neighboring Sudan, Leland’s plane crashed into a

mountainside in Ethiopia. The force of the crash killed everyone aboard,

including the Congressman, his chief of staff Patrice Johnson, and 13 other

passengers from a number of government, humanitarian, and development

organizations.

George Thomas “Mickey” Leland ▪ Born

November 27, 1944, Lubbock, TX▪ Died

August 8,1989, Gambela, Ethiopia. Resersh more about the great Amerivan and

share with your babies. Make it a cahmpion day1

August 7 1906- Ernest Wade

GM- FBF – Today I would like to share with you. Ernest Wade (August 7, 1906 – April 15, 1983) who was an American actress who is best known for playing the role of Sapphire Stevens on both the radio and TV versions of The Amos ‘n’ Andy Show. It was work but since there is name calling Ernest ( Nigger) I will leave here one day. Enjoy!

Remember ” A lot of people have given up having any hopes and dreams in exchange for escaping from reality. No wonder the world is such a bleak place; no one is doing anything about it.” – Ernest Wade

Today in our History – August 7,1906 – Is dead.

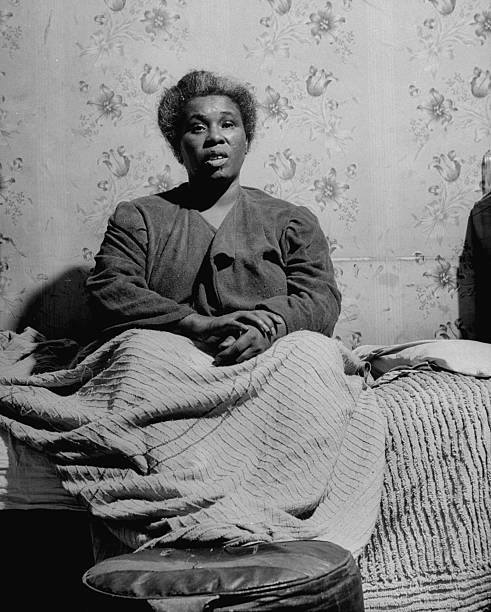

Born in Jackson, Mississippi, Wade was trained as a singer and

organist. Her family had a strong connection to the theater. Her mother, Hazel

Wade, worked in vaudeville as a performer, while her maternal grandmother, Mrs.

Johnson, worked for the Lincoln Theater in Baltimore, Maryland

Ernestine grew up in Los Angeles and started her acting career at age four. In

1935, Ernestine was a member of the Four Hot Chocolates singing group.

She appeared in bit parts in films and did the ve performance of a butterfly in the 1946 Walt Disney production Song of the South. Wade was a member of the choir organized by actress-singer Anne Brown for the filming of the George Gershwin biographical film Rhapsody in Blue (1945) and appeared in the film as one of the “Catfish Row” residents in the Porgy and Bess segment. She enjoyed the highest level of prominence on Amos ‘n Andy by playing the shrewish, demanding and manipulative wife of George “Kingfish” Stevens. Wade, Johnny Lee, and Lillian Randolph, Amanda Randolph, Jester Hairston, Roy Glenn (and several others) were among the Amos ‘n’ Andy radio cast members to also appear in the TV series.

Ernestine began playing Sapphire Stevens in 1939, but riginally

came to the Amos ‘n’ Andy radio show in the rolof Valada Green, a lady who

believed she had married Andy.

In her interview which is part of the documentary Amos ‘n’ Andy: Anatomy of a

Controversy, Wade related how she got the job with the radio show. Initially there

for a singing role, she was asked if she could “do lines”. When the

answer was yes, she was first asked to say “I do” and then to scream;

the scream got her the role of Valada Green. Ernestine also played the radio

roles of The Widow Armbruster, Sara Fletcher, and Mrs. Van Porter.

In a 1979 interview, Ernestine related that she would often be stopped by strangers who recognized her from the television show, saying, “I know who you are and I want to ask you, is that your real husband?” At her home, she had framed signed photos from the members of the Amos ‘n’ Andy television show cast. Tim Moore, her TV husband, wrote the following on his, “My Best Wishes To My Darling Battle Ax From The Kingfish Tim Moore”.

Wade defended her character against criticism of being a negative stereotype of African American women. In a 1973 interview, she stated, “I know there were those who were offended by it, but I still have people stop me on the street to tell me how much they enjoyed it. And many of those people are black members of the NAACP.” The documentary Amos ‘n’ Andy: Anatomy of a Controversy covered the history of the radio and television shows as well as interviews with surviving cast members. Ernestine was among them, and she continued her defense of the show and those with roles in it.

She believed that the roles she and her colleagues played

made it possible for African-American actors who came later to be cast in a

wider variety of roles. She also considered the early typecast roles, where

women were most often cast as maids, not to be damaging, seeing them in the

sense of someone being either given the role of the hero or the part of the

villain.

In later years, she continued as an actress, doing more voice work for radio and cartoons. After Amos ‘n’ Andy, Wade did voice work in television and radio commercials. Ernestine also did office work and played the organ. She also appeared in a 1967 episode of TV’s Family Affair as a maid working for a stage actress played by Joan Blondell.

Ernestine Wade is buried in Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery in Los Angeles, California. Since she had no headstone, the West Adams Heritage Association marked her grave with a plaque. Reacearh more about this great American and make it a champion day!

August 6 1948- The trenton six

GM – FBF – Today, I am going to share with you a story that

happened in my hometown of Trenton, N.J., this story would go down as one of

the most controversial court cases not only in local history but up and down

the East Coast along with National news but also International news for its

time. A young Thurgood Marshall was in Trenton to defend the young blacks.

men.

W.E.B. Dubois, Paul Roberson to Albert Einstein communicated

their support to local civil rights leader

Catherine “Stoney” Graham.

Remember – “if any of these niggers gets off, we might as well give up and turn in our badges.” – Unidentified Trenton Police Officer

Today in our History – August 6, 1948 – The Trenton Six is the group name for six African-American defendants tried for murder of an elderly white shopkeeper in January 1948 in Trenton, New Jersey. The six young men were convicted on August 6, 1948 by an all-white jury of the murder and sentenced to death.

Their case was taken up as a major civil rights case, because of injustices after their arrests and questions about the trial. The Civil Rights Congress and the NAACP had legal teams that represented three men each in appeals to the State Supreme Court. It found fault with the court’s instruction to the jury, and remanded the case to a lower court for retrial, which took place in 1951. That resulted in a mistrial, requiring a third trial. Four of the defendants were acquitted. Ralph Cooper pleaded guilty, implicating the other five in the crime. Collis English was convicted of murder, but the jury recommended mercy – life in prison rather than execution.

The civil rights groups appealed again to the State Supreme Court, which found fault with the court, and remanded the case to the lower court for retrial of the two defendants who were sentenced to life. One was convicted in 1952 and the other pleaded guilty; both were sentenced to life. Collis English died in late December that year in prison. Ralph Cooper was paroled in 1954 and disappeared from the records.

On the morning of January 27, 1948, the elderly William Horner

(1875–1948) opened his second-hand furniture store as usual, at 213 North Broad

Street in Trenton. His common-law wife worked with him there. A while later,

several young African-American men entered the store. One or more killed Horner

by hitting him in the head with a soda bottle; some also assaulted his wife.

She could not say for sure how many men were involved with the attack, saying

two to four light-skinned African-American males in their teens had assaulted

them.

The Trenton police, pressured to solve the case, arrested the following men:

Ralph Cooper, 24; Collis English, 23; McKinley Forrest, 35; John McKenzie, 24;

James Thorpe, 24; and Horace Wilson, 37, on February 11, 1948. All were

arrested without warrants, were held without being given access to attorneys,

and were questioned for as long as four days before being brought before a

judge. Five of the six men charged with the murder signed confessions written

by the police.

The trial began on June 7, 1948, when the State of New Jersey

opened its case against the six based on the five signed confessions obtained

by the Trenton police. There was no other forensic evidence, and Horner’s widow

could not identify the men as the ones in her store.

The defendants were assigned four attorneys, one of whom was African American.

On August 6, 1948 all six men were convicted and sentenced to death. All six

had provided alibis for that day and had repudiated their confessions, signed

under duress. An appeal was filed and an automatic stay of execution granted.

In the process of appeal, the Communist Party USA took on the legal defense of half the defendants, with Emanuel Hirsch Bloch acting as their attorney.

The NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) defended the other three men, seeking to get their convictions overturned. Among the NAACP attorneys were Thurgood Marshall, who led many legal efforts by the organization; he later was appointed as the first African American to the Supreme Court of the United States; Clifford Roscoe Moore, Sr., later appointed as U.S. Commissioner for Trenton, New Jersey, the first African American appointed to such a position since post-Civil War Reconstruction; and Raymond Pace Alexander, later to be appointed as a judge in Pennsylvania.

In 1949 the State Supreme Court remanded the case to the lower court for retrial, ruling that the jury had been improperly charged in the first case.[2] In the course of the trial, the defense teams revealed that evidence had been manufactured. The medical examiner in Trenton was found guilty of perjury.

After a mistrial, four of the men were acquitted in a third

trial.

Collis English was convicted. Ralph Cooper pleaded guilty, implicating the

other five in the crime. The jury recommended mercy for these two men, with

prison sentences rather than capital punishment. These two convictions were

also appealed; the State Supreme Court said the court had erred again. It

remanded the case to the lower court for a fourth trial in 1952.

English suffered a heart attack (myocardial infarction) soon after the trial and died in December 1952 in prison. Cooper served a portion of his prison sentence and was released on parole in 1954 for good behavior.

Because of legal abuses in the treatment of suspects after the arrests, the case attracted considerable attention. The Civil Rights Congress and the NAACP generated publicity to highlight the racial inequities in the railroading of the suspects, their lack of access to counsel, the chief witness’ inability to identify them, and other issues. Figures such as W. E. B. Du Bois to Pete Seeger, then active in leftist movements, joined the campaign for publicity about obtaining justice in the trials of these men. Albert Einstein also protested the injustice. Commentary and protests were issued from many nations.

The Accused

• Ralph Cooper (1924-?) pleaded guilty in the 4th trial and was sentenced to

life. After being paroled in 1954, he disappeared from records.

• Collis English (1925–1952). Shortly after the fourth trial, he died in prison

on December 31, 1952 of a heart attack.

• McKinley Forrest (1913–1982). He was the brother-in-law of Collis English.

Acquitted in the third trial in 1951.

• John McKenzie (1925-?), acquitted in 1951.

• James Henry Thorpe, Jr. (1913–1955), acquitted in 1951. He died in a car

crash on March 25, 1955.[5]

• Horace Wilson (1911–2000), acquitted in 1951.

Have a saecial place for her to give for a great cause, make it a champion day A look back at – A “Northern Lynching,” 1948 – 70 years later – Remembering the Trenton Six Case – Read and Learn!