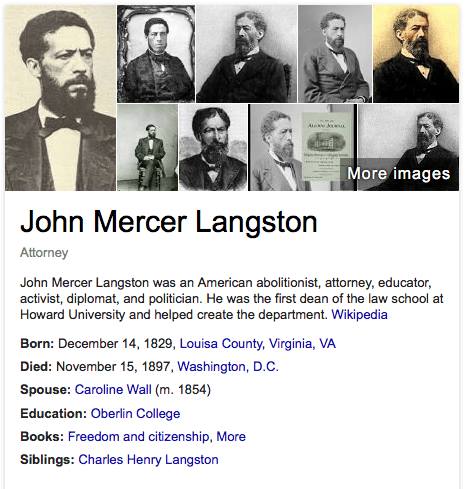

GM – FBF – “The black people of America, will rise up

through proper education.” – John Mercer Langston

Remember – “A nation may lose its liberties and be a

century in finding it out. Where is the American liberty? … In its

far-reaching and broad sweep, slavery has stricken down the freedom of us

all.” – John Mercer Langston

Today in our History – April 2, 1872. John Mercer Langston,

serve as dean of Howard University’s law school; it was the first black law

school in the country. Appointed acting president of the school in 1872.

Together with his older brothers Gideon and Charles, John

Langston became active in the abolitionist movement. He helped runaway slaves

to escape to the North along the Ohio part of the Underground Railroad. In 1858

he and Charles partnered in leading the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society, with John

acting as president and traveling to organize local units, and Charles managing

as executive secretary in Cleveland.

In 1863 when the government approved founding of the United

States Colored Troops, John Langston was appointed to recruit African Americans

to fight for the Union Army. He enlisted hundreds of men for duty in the

Massachusetts Fifty-fourth and Fifty-fifth regiments, in addition to 800 for

Ohio’s first black regiment. Even before the end of the war, Langston worked

for issues of black suffrage and opportunity. He believed that black men’s

service in the war had earned their right to vote, and that it was fundamental

to their creating an equal place in society.

After the war, Langston was appointed inspector general for the

Freedmen’s Bureau, a Federal organization that assisted freed slaves and tried

to oversee labor contracts. The Bureau also ran a bank and helped establish

schools for freedmen and their children.

In 1864 Langston chaired the committee whose agenda was ratified

by the black National Convention: they called for abolition of slavery, support

of racial unity and self-help, and equality before the law. To accomplish this

program, the convention founded the National Equal Rights League and elected

Langston president. He served until 1868. Like the later National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the League was based in state

and local organizations. Langston traveled widely to build support. “By war’s

end, nine state auxiliaries had been established; some twenty months later,

Langston could boast of state leagues nearly everywhere.”

In 1868 Langston moved to Washington, D.C. to establish and

serve as dean of Howard University’s law school; it was the first black law

school in the country. Appointed acting president of the school in 1872, and

vice president of the school, Langston worked to establish strong academic

standards. He also engendered the kind of open environment he had known at

Oberlin College. Langston was passed over for the permanent position of

president of Howard University School of Law by a committee that refused to

disclose the reason.

During 1870, Langston assisted Republican Senator Charles Sumner

from Massachusetts with drafting the civil rights bill that was enacted as the

Civil Rights Act of 1875. The 43rd Congress of the United States passed the

bill in February 1875 and it was signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant

on March 1, 1875.

President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Langston a member of the

Board of Health of the District of Columbia.

In 1877 President Rutherford Hayes appointed Langston as U.S.

Minister to Haiti; he also served as chargé d’affaires to the Dominican

Republic.

After his diplomatic service, in 1885 Langston returned to the

US and Virginia. He was appointed by the state legislature as the first

president of Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute, a historically black

college (HBCU) at Petersburg. There he also began to build a political base.

In 1888, Langston was urged to run for a seat in the U.S. House

of Representatives by fellow Republicans, both black and white. Leaders of the

biracial Readjuster Party, which had held political power in Virginia from 1879

to 1883, did not support his candidacy. Langston ran as a Republican and lost

to his Democratic opponent. He contested the results of the election because of

voter intimidation and fraud.

After 18 months, the Congressional elections committee declared

Langston the winner, and he took his seat in the U.S. Congress. He served for

the remaining six months of the term, but lost his bid for reelection as

Democrats regained control of Virginia. Langston was the first black person

elected to Congress from Virginia, and he was the last for another century. In

a period of increasing disenfranchisement of blacks in the South, he was one of

five African Americans elected to Congress during the Jim Crow era of the last

decade of the nineteenth century. Two were elected from South Carolina and two

from North Carolina. After them, no African Americans would be elected to

Congress from the South until 1972, after passage of federal civil rights

legislation enforcing constitutional rights for all citizens.

In 1890 Langston was named as a member of the board of trustees

of St. Paul Normal and Industrial School, a historically black college, when it

was incorporated by the Virginia General Assembly. In this period, he also

wrote his autobiography, which he published in 1894.

From 1891 until his death in 1897, he practiced law in

Washington, D.C. He died at his home, Hillside Cottage at 2225 Fourth Street NW

in Washington, DC, on the morning of November 15 from malaria induced acute

indigestion. After spending time at Harmony Cemetery in Maryland, and despite

talk of sending him to Nashville for burial, he was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery

in Washington, DC.

Langston’s house in Oberlin

has been designated as a National Historic Landmark, Langston was the

great-uncle of the poet James Mercer Langston Hughes (called Langston Hughes).

Research more about this great American and share with your babies and make it

a champion day!