GM – FBF – Today I would like to share with you a story that was

so bad, the President hurt many people of color and their families. It would be

know as the Brownsville Case. Enjoy!

Remember – ” I lost my livelthood and my future because of

a lie! – Black Solder

Today in our History – August 13, 1906 – Black soldiers accused

of killing a white bartender and a Hispanic police officer was wounded by

gunshots in the town.

Since arriving at Fort Brown on July 28, 1906, the black US

soldiers had been required to follow the legal color line mandate from white

citizens of Brownsville, which included the state’s racial segregation law

dictating separate accommodation for black people and white people, and Jim

Crow customs such as showing respect for white people, as well as respect for

local laws.

]

A reported attack on a white woman during the night of August 12 so incensed

many townspeople that Maj. Charles W. Penrose, after consultation with Mayor

Frederick Combe, declared an early curfew for soldiers the following day to

avoid trouble.

On the night of August 13, 1906, a white bartender was killed

and a Hispanic police officer was wounded by gunshots in the town. Immediately

the residents of Brownsville cast the blame on the black soldiers of the 25th

Infantry at Fort Brown. But the all-white commanders at Fort Brown confirmed

that all of the soldiers were in their barracks at the time of the shootings.

Local whites, including Brownsville’s mayor, still claimed that some of the

black soldiers participated in the shooting.

Local townspeople of Brownsville began providing evidence of the 25th

Infantry’s part in the shooting by producing spent bullet cartridges from Army

rifles which they said belonged to the 25th’s men. Despite the contradictory

evidence that demonstrated the spent shells were planted in order to frame men

of the 25th Infantry in the shootings, investigators accepted the statements of

the local whites and the Brownsville mayor.

When soldiers of the 25th Infantry were pressured to name who

fired the shots, they insisted that they had no idea who had committed the

crime. Captain Bill McDonald of the Texas Rangers investigated 12 enlisted men

and tried to tie the case to them. The local county court did not return any

indictments based on his investigation, but residents kept up complaints about

the black soldiers of the 25th.

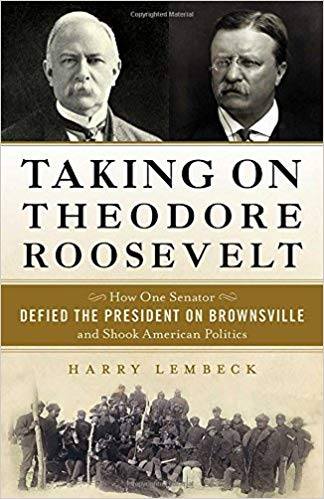

At the recommendation of the Army’s Inspector General, President

Theodore Roosevelt ordered 167 of the black troops to be dishonorably discharged

because of their “conspiracy of silence”. Although some accounts have

claimed that six of the troops were Medal of Honor recipients, historian Frank

N. Schubert has shown that none was. Fourteen of the men were later reinstated

into the army. The dishonorable discharge prevented the 153 other men from ever

working in a military or civil service capacity. Some of the black soldiers had

been in the U.S. Army for more than 20 years, while others were extremely close

to retirement with pensions, which they lost as a result.

The prominent African-American educator and activist, Booker T.

Washington, president of Tuskegee Institute, got involved in the case. He asked

President Roosevelt to reconsider his decision in the affair. Roosevelt

dismissed Washington’s plea and allowed his decision to stand.

Both blacks and many whites across the United States were

outraged at Roosevelt’s actions. The black community began to turn against him,

although it had previously supported the Republican president (in addition to maintaining

loyalty to the party of Abraham Lincoln, black people approved of Roosevelt

having invited Booker T. Washington to dinner at the White House and speaking

out publicly against lynching). The administration withheld news of the

dishonorable discharge of the soldiers until after the 1906 Congressional

elections, so that the pro-Republican black vote would not be affected. The

case became a political football, with William Howard Taft, positioning for the

next candidacy for presidency, trying to avoid trouble.

Leaders of major black organizations, such as the Constitution

League, the National Association of Colored Women, and the Niagara Movement,

tried to persuade the administration not to discharge the soldiers, but were

unsuccessful. From 1907–1908, the US Senate Military Affairs Committee

investigated the Brownsville Affair, and the majority in March 1908 reached the

same conclusion as Roosevelt. Senator Joseph B. Foraker of Ohio had lobbied for

the investigation and filed a minority report in support of the soldiers’

innocence. Another minority report by four Republicans concluded that the

evidence was too inconclusive to support the discharges. In September 1908,

prominent educator and leader W. E. B. DuBois urged black people to register to

vote and to remember their treatment by the Republican administration when it

was time to vote for president.

Feelings across the nation remained high against the government

actions, but with Taft succeeding Roosevelt as President, and Foraker failing

to win re-election, some of the political pressure declined.

On February 23, 1909, the Committee on Military Affairs

recommended favorably on Bill S.5729 for correction of records and reenlistment

of officers and men of Companies B, C, and D of the 25th Infantry.

Senator Foraker was not re-elected. He continued to work on the

Brownsville affair during his remaining time in office, guiding a resolution

through Congress to establish a board of inquiry with the power to reinstate

the soldiers. The bill, which the administration did not oppose, was less than

Foraker wanted. He had hoped for a requirement that unless specific evidence

was shown against a man, he would be allowed to re-enlist. The legislation

passed both houses, and was signed by Roosevelt on March 2, 1909.

On March 6, 1909, shortly after he left the Senate, Foraker was

the guest of honor at a mass meeting at Washington’s Metropolitan African

Methodist Episcopal Church. Though both whites and African Americans assembled

to recognize the former senator, all the speakers but Foraker were African

American. Presented with a silver loving cup, he addressed the crowd,

I have said that I do not believe that a man in that battalion

had anything to do with the shooting up of “Brownsville,” but whether

any one of them had, it was our duty to ourselves as a great, strong, and

powerful nation to give every man a hearing, to deal fairly and squarely with

every man; to see to it that justice was done to him; that he should be heard.

On April 7, 1909, under the provisions of the Act of March 30,

1909, a Military Court of Inquiry was set up by Secretary of War Jacob M.

Dickinson to report on the charges and recommend for reenlistment those men who

had been discharged under Special Order # 266, November 9, 1906. Of the 167 discharged

men, 76 were located as witnesses, and 6 did not wish to appear.

The 1910 Court of Military Inquiry undertook an examination of

the soldiers’ bids for re-enlistment, in view of the Senate committee’s

reports, but its members interviewed only about one-half of the soldiers

discharged. It accepted 14 for re-enlistment, and eleven of these re-entered

the Army.[4][10]

The government did not re-examine the case until the early 1970s.

In 1970, historian John D. Weaver published The Brownsville

Raid, which investigated the affair in depth. Weaver argued that the accused

members of the 25th Infantry were innocent and that they were discharged

without benefit of due process of law as guaranteed by the United States

Constitution. After reading his book, Congressman Augustus F. Hawkins of Los

Angeles introduced a bill to have the Defense Department re-investigate the

matter to provide justice to the accused soldiers.

In 1972, the Army found the

accused members of the 25th Infantry to be innocent. At its recommendations,

President Richard Nixon pardoned the men and awarded them honorable discharges,

without backpay. These discharges were generally issued posthumously, as there

were only two surviving soldiers from the affair: one had re-enlisted in 1910.

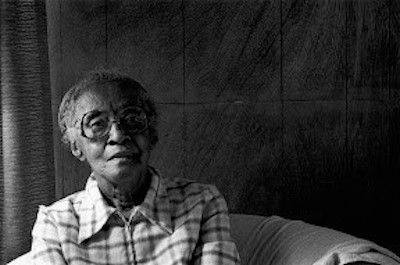

In 1973, Hawkins and Senator Hubert Humphreygained congressional passage of a

tax-free pension for the last survivor, Dorsie Willis, who received $25,000. He

was honored in ceremonies in Washington, DC, and Los Angeles. Research more

about the case and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!