GM – FBF – Today, I am going to share with you a story that

happened in my hometown of Trenton, N.J., this story would go down as one of

the most controversial court cases not only in local history but up and down

the East Coast along with National news but also International news for its

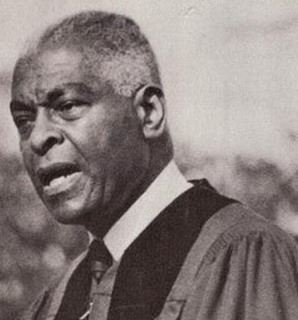

time. A young Thurgood Marshall was in Trenton to defend the young blacks.

men.

W.E.B. Dubois, Paul Roberson to Albert Einstein communicated

their support to local civil rights leader

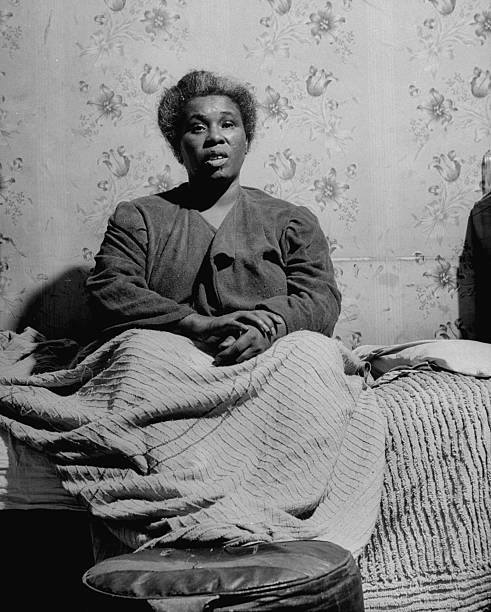

Catherine “Stoney” Graham.

Remember – “if any of these niggers gets off, we might as well give up and turn in our badges.” – Unidentified Trenton Police Officer

Today in our History – August 6, 1948 – The Trenton Six is the group name for six African-American defendants tried for murder of an elderly white shopkeeper in January 1948 in Trenton, New Jersey. The six young men were convicted on August 6, 1948 by an all-white jury of the murder and sentenced to death.

Their case was taken up as a major civil rights case, because of injustices after their arrests and questions about the trial. The Civil Rights Congress and the NAACP had legal teams that represented three men each in appeals to the State Supreme Court. It found fault with the court’s instruction to the jury, and remanded the case to a lower court for retrial, which took place in 1951. That resulted in a mistrial, requiring a third trial. Four of the defendants were acquitted. Ralph Cooper pleaded guilty, implicating the other five in the crime. Collis English was convicted of murder, but the jury recommended mercy – life in prison rather than execution.

The civil rights groups appealed again to the State Supreme Court, which found fault with the court, and remanded the case to the lower court for retrial of the two defendants who were sentenced to life. One was convicted in 1952 and the other pleaded guilty; both were sentenced to life. Collis English died in late December that year in prison. Ralph Cooper was paroled in 1954 and disappeared from the records.

On the morning of January 27, 1948, the elderly William Horner

(1875–1948) opened his second-hand furniture store as usual, at 213 North Broad

Street in Trenton. His common-law wife worked with him there. A while later,

several young African-American men entered the store. One or more killed Horner

by hitting him in the head with a soda bottle; some also assaulted his wife.

She could not say for sure how many men were involved with the attack, saying

two to four light-skinned African-American males in their teens had assaulted

them.

The Trenton police, pressured to solve the case, arrested the following men:

Ralph Cooper, 24; Collis English, 23; McKinley Forrest, 35; John McKenzie, 24;

James Thorpe, 24; and Horace Wilson, 37, on February 11, 1948. All were

arrested without warrants, were held without being given access to attorneys,

and were questioned for as long as four days before being brought before a

judge. Five of the six men charged with the murder signed confessions written

by the police.

The trial began on June 7, 1948, when the State of New Jersey

opened its case against the six based on the five signed confessions obtained

by the Trenton police. There was no other forensic evidence, and Horner’s widow

could not identify the men as the ones in her store.

The defendants were assigned four attorneys, one of whom was African American.

On August 6, 1948 all six men were convicted and sentenced to death. All six

had provided alibis for that day and had repudiated their confessions, signed

under duress. An appeal was filed and an automatic stay of execution granted.

In the process of appeal, the Communist Party USA took on the legal defense of half the defendants, with Emanuel Hirsch Bloch acting as their attorney.

The NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) defended the other three men, seeking to get their convictions overturned. Among the NAACP attorneys were Thurgood Marshall, who led many legal efforts by the organization; he later was appointed as the first African American to the Supreme Court of the United States; Clifford Roscoe Moore, Sr., later appointed as U.S. Commissioner for Trenton, New Jersey, the first African American appointed to such a position since post-Civil War Reconstruction; and Raymond Pace Alexander, later to be appointed as a judge in Pennsylvania.

In 1949 the State Supreme Court remanded the case to the lower court for retrial, ruling that the jury had been improperly charged in the first case.[2] In the course of the trial, the defense teams revealed that evidence had been manufactured. The medical examiner in Trenton was found guilty of perjury.

After a mistrial, four of the men were acquitted in a third

trial.

Collis English was convicted. Ralph Cooper pleaded guilty, implicating the

other five in the crime. The jury recommended mercy for these two men, with

prison sentences rather than capital punishment. These two convictions were

also appealed; the State Supreme Court said the court had erred again. It

remanded the case to the lower court for a fourth trial in 1952.

English suffered a heart attack (myocardial infarction) soon after the trial and died in December 1952 in prison. Cooper served a portion of his prison sentence and was released on parole in 1954 for good behavior.

Because of legal abuses in the treatment of suspects after the arrests, the case attracted considerable attention. The Civil Rights Congress and the NAACP generated publicity to highlight the racial inequities in the railroading of the suspects, their lack of access to counsel, the chief witness’ inability to identify them, and other issues. Figures such as W. E. B. Du Bois to Pete Seeger, then active in leftist movements, joined the campaign for publicity about obtaining justice in the trials of these men. Albert Einstein also protested the injustice. Commentary and protests were issued from many nations.

The Accused

• Ralph Cooper (1924-?) pleaded guilty in the 4th trial and was sentenced to

life. After being paroled in 1954, he disappeared from records.

• Collis English (1925–1952). Shortly after the fourth trial, he died in prison

on December 31, 1952 of a heart attack.

• McKinley Forrest (1913–1982). He was the brother-in-law of Collis English.

Acquitted in the third trial in 1951.

• John McKenzie (1925-?), acquitted in 1951.

• James Henry Thorpe, Jr. (1913–1955), acquitted in 1951. He died in a car

crash on March 25, 1955.[5]

• Horace Wilson (1911–2000), acquitted in 1951.

Have a saecial place for her to give for a great cause, make it a champion day A look back at – A “Northern Lynching,” 1948 – 70 years later – Remembering the Trenton Six Case – Read and Learn!