Today in our History – Most people who have to cut their lawns

are grateful in many ways but during the turn of the Century

many looked unfavorably towards him because someone else they thought should

have got the Idea first.As we know this America who makes your weekends go

faster was the person who put in the patent first. Let’s read about the

Inventor. Enjoy!

REMEMBER – I have always said that American who are blessed with morden eqiotment will always beat the one who doesn’t. – John Albert Burr

Today in our History -June 7, 1905 – Do you know which company was the first to hold a meeting with John Albert Burr?. Briggs & Straton Company – Wisconsin.

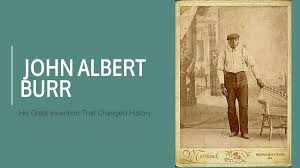

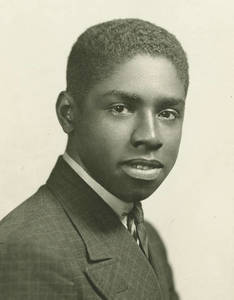

If you have a manual push mower today, it likely uses design elements from 19th Century black American inventor John Albert Burr’s patented rotary blade lawn mower.

On May 9, 1899, John Albert Burr patented an improved rotary blade lawn mower. Burr designed a lawn mower with traction wheels and a rotary blade that was designed to not easily get plugged up from lawn clippings. John Albert Burr also improved the design of lawn mowers by making it possible to mow closer to building and wall edges.

You can view U.S. patent 624,749 issued to John Albert Burr.

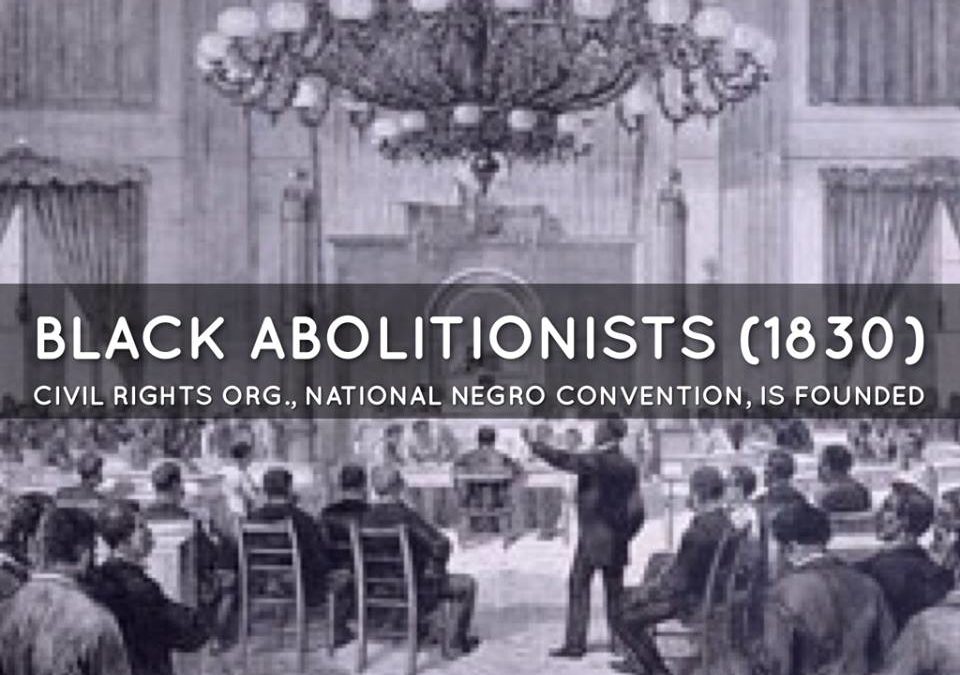

John Burr was born in Maryland in 1848, at a time when he would have been a teenager during the Civil War. His parents were slaves who were later freed, and he may also have been a slave until age 17. He didn’t escape from manual labor, as he worked as a field hand during his teenage years.

But his talent was recognized and wealthy black activists ensured he was able to attend engineering classes at a private university. He put his mechanical skills to work making a living repairing and servicing farm equipment and other machines. He moved to Chicago and also worked as a steelworker. When he filed his patent for the rotary mower in 1898, he was living in Agawam, Massachusetts.

“The object of my invention is to provide a casing which wholly encloses the operating gearing so as to prevent it from becoming choked by the grass or clogged by obstructions of any kind,” reads the patent application.

His rotary lawn mower design helped reduce the irritating clogs of clippings that are the bane of manual mowers. It was also more maneuverable and could be used for closer clipping around objects such as posts and buildings. Looking at his patent diagram, you will see a design that is very familiar for manual rotary mowers today.

Powered mowers for home use were still decades away. As lawns become smaller in many newer neighborhoods, many people are returning to manual rotary mowers like Burr’s design.

Burr continued to patent improvements to his design. He also designed devices for mulching clippings, sifting, and dispersing them. Today’s mulching power mowers may be part of his legacy, returning nutrients to the turf rather than bagging them for compost or disposal. In this way, his inventions helped save labor and were also good for the grass. He held over 30 U.S. patents for lawn care and agricultural inventions.

Burr enjoyed the fruits of his success. Unlike many inventors who never see their designs commercialized, or soon lose any benefits, he got royalties for his creations. He enjoyed traveling and lecturing. He lived a long life and died in 1926 of influenza at age 78.

Next time you mow the lawn, acknowledge the inventor who made the task a little easier. Read more of the great American and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!