GM – FBF – Knowledge through proper education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school.

Remember – People needed an easier way to deliver Ice Cream to the dish, so I made everyone happy but no one ever said thank you in all these years. – Alfred Louis Cralle

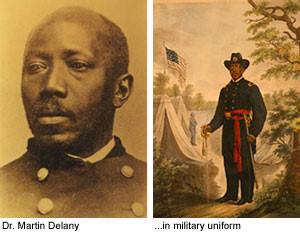

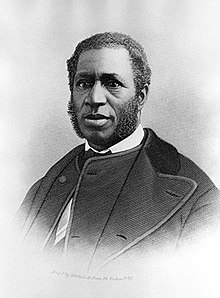

Today in our History – February 2, 1897 – Alfred L. Cralle (1866–1920) was an African American businessman and inventor who was best known for inventing the ice cream scoop in 1897. Cralle was born on September 4, 1866, in Kenbridge, Lunenburg County, Virginia, just after the end of the American Civil War. He attended local schools and worked for his father in the carpentry trade as a young man. During that period, he also became interested in mechanics.

Cralle was sent to Washington D.C. where he attended Wayland Seminary, a branch of the National Theological Institute, one of a number of schools founded by the American Baptist Home Mission Society immediately after the Civil War to help educate newly freed African Americans.

After attending the school for a few years, Cralle moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he worked as a porter at a drugstore and at a hotel. While working at the hotel, he developed the idea of the ice cream scoop. It came to him when he noticed ice cream servers having difficulty trying to get the popular confection desired by the customer into the cone they were usually holding. The ice cream tended to stick to spoons and ladles, usually requiring the server to use two hands and at least two separate implements to serve customers.

Cralle responded to that problem by creating a mechanical device now known as the ice cream scoop. He applied for and received a patent on February 2, 1897. The thirty-year-old was granted U.S. Patent #576395.

Cralle’s invention, originally called an Ice Cream Mold and Disher, was designed to be able to keep ice cream and other foods from sticking. It was easy to operate with one hand. Since the Mold and Disher was strong and durable, effective, and inexpensive, it could be constructed in almost any desired shape, such as cone or a mound, with no delicate parts that could break or malfunction.

Cralle was also a successful Pittsburgh business promoter as well. When local black investors created the Afro-American Financial, Accumulating, Merchandise, and Business Association in Pittsburgh, he was selected as assistant manager.

He did not become famous for his inventing of his ice cream scoop. It spread widely so quickly that people soon forgot or never knew Cralle as the inventor. Thus he never profited from his invention.

Married and with three children, Cralle experienced a number of personal tragedies. His wife and one of his daughters died in 1918 of a communicable disease. In 1920 he lost his only son to another disease. With their deaths, Cralle’s only surviving immediate family member was daughter Anna Cralle, born in 1910. Later in 1920, Cralle himself was killed in an automobile accident in Pittsburgh. Research more about this great American and how one of America’s favorite deserts became easier to enjoy and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!