GM – FBF – I had a client in Anniston, Alabama for four (4)

years. Every visit I always asked where is the monument for the freedom riders

who’s bus was set ablaze? I asked hotel workers, local business owners, schools

principls, etc. that was 2011 through 2015. I am happy to announce that on

January 12, 2017, The Freedom Riders National Monument in Anniston, Alabama

opened. Enjoy!

Remember – “Traveling in the segregated South for black

people was humiliating. The very fact that there were separate facilities was

to say to black people and white people that blacks were so subhuman and so

inferior that we could not even use public facilities that white people used.”

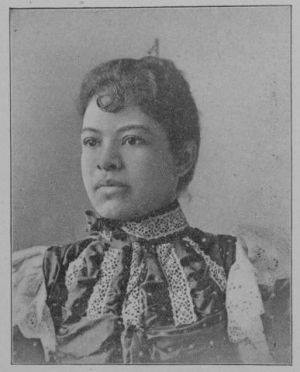

~ Diane Nash, Freedom Rides Organizer

Today in our History – May 4, 1961 – The original group of 13

Freedom Riders—seven African Americans and six whites—left Washington, D.C., on

a Greyhound bus on May 4, 1961.

Freedom Riders were groups of white and African American civil

rights activists who participated in Freedom Rides, bus trips through the

American South in 1961 to protest segregated bus terminals. Freedom Riders

tried to use “whites-only” restrooms and lunch counters at bus stations in

Alabama, South Carolina and other Southern states. The groups were confronted

by arresting police officers—as well as horrific violence from white

protestors—along their routes, but also drew international attention to their

cause.

The 1961 Freedom Rides, organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE),

were modeled after the organization’s 1947 Journey of Reconciliation. During

the 1947 action, African-American and white bus riders tested the 1946 U.S.

Supreme Court decision in Morgan v. Virginia that found segregated bus seating

was unconstitutional.

The 1961 Freedom Rides sought to test a 1960 decision by the

Supreme Court in Boynton v. Virginia that segregation of interstate

transportation facilities, including bus terminals, was unconstitutional as

well. A big difference between the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation and the 1961

Freedom Rides was the inclusion of women in the later initiative.

In both actions, black riders traveled to the American

South—where segregation continued to occur—and attempted to use whites-only

restrooms, lunch counters and waiting rooms.

The original group of 13 Freedom Riders—seven African Americans

and six whites—left Washington, D.C., on a Greyhound bus on May 4, 1961. Their

plan was to reach New Orleans, Louisiana, on May 17 to commemorate the seventh

anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, which

ruled that segregation of the nation’s public schools was unconstitutional.

The group traveled through Virginia and North Carolina, drawing

little public notice. The first violent incident occurred on May 12 in Rock

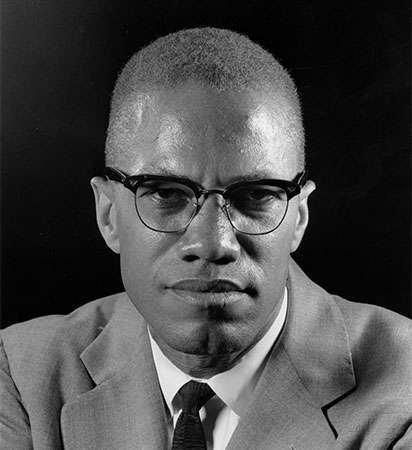

Hill, South Carolina. John Lewis, an African-American seminary student and

member of the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), white Freedom

Rider and World War II veteran Albert Bigelow, and another African-American

rider were viciously attacked as they attempted to enter a whites-only waiting

area.

The next day, the group reached Atlanta, Georgia, where some of

the riders split off onto a Trailways bus.

John Lewis, one of the original group of 13 Freedom Riders, was

elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in November 1986. Lewis, a

Democrat, has continued to represent Georgia’s 5th Congressional District,

which includes Atlanta, into the early part of the 21st century.

On May 14, 1961, the Greyhound bus was the first to arrive in

Anniston, Alabama. There, an angry mob of about 200 white people surrounded the

bus, causing the driver to continue past the bus station.

The mob followed the bus in automobiles, and when the tires on

the bus blew out, someone threw a bomb into the bus. The Freedom Riders escaped

the bus as it burst into flames, only to be brutally beaten by members of the

surrounding mob.

The second bus, a Trailways vehicle, traveled to Birmingham,

Alabama, and those riders were also beaten by an angry white mob, many of whom

brandished metal pipes. Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor

stated that, although he knew the Freedom Riders were arriving and violence

awaited them, he posted no police protection at the station because it was

Mother’s Day.

Photographs of the burning Greyhound bus and the bloodied riders

appeared on the front pages of newspapers throughout the country and around the

world the next day, drawing international attention to the Freedom Riders’

cause and the state of race relations in the United States.

Following the widespread violence, CORE officials could not find

a bus driver who would agree to transport the integrated group, and they

decided to abandon the Freedom Rides. However, Diane Nash, an activist from the

SNCC, organized a group of 10 students from Nashville, Tennessee, to continue

the rides.

U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, brother of President

John F. Kennedy, began negotiating with Governor John Patterson of Alabama and

the bus companies to secure a driver and state protection for the new group of

Freedom Riders. The rides finally resumed, on a Greyhound bus departing

Birmingham under police escort, on May 20.

The violence toward the Freedom Riders was not quelled—rather,

the police abandoned the Greyhound bus just before it arrived at the

Montgomery, Alabama, terminal, where a white mob attacked the riders with

baseball bats and clubs as they disembarked. Attorney General Kennedy sent 600

federal marshals to the city to stop the violence.

The following night, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

led a service at the First Baptist Church in Montgomery, which was attended by

more than one thousand supporters of the Freedom Riders. A riot ensued outside

the church, and King called Robert Kennedy to ask for protection.

Kennedy summoned the federal marshals, who used teargas to

disperse the white mob. Patterson declared martial law in the city and

dispatched the National Guard to restore order.

On May 24, 1961, a group of Freedom Riders departed Montgomery

for Jackson, Mississippi. There, several hundred supporters greeted the riders.

However, those who attempted to use the whites-only facilities were arrested

for trespassing and taken to the maximum-security penitentiary in Parchman,

Mississippi.

During their hearings, the judge turned and looked at the wall

rather than listen to the Freedom Riders’ defense—as had been the case when

sit-in participants were arrested for protesting segregated lunch counters in

Tennessee. He sentenced the riders to 30 days in jail.

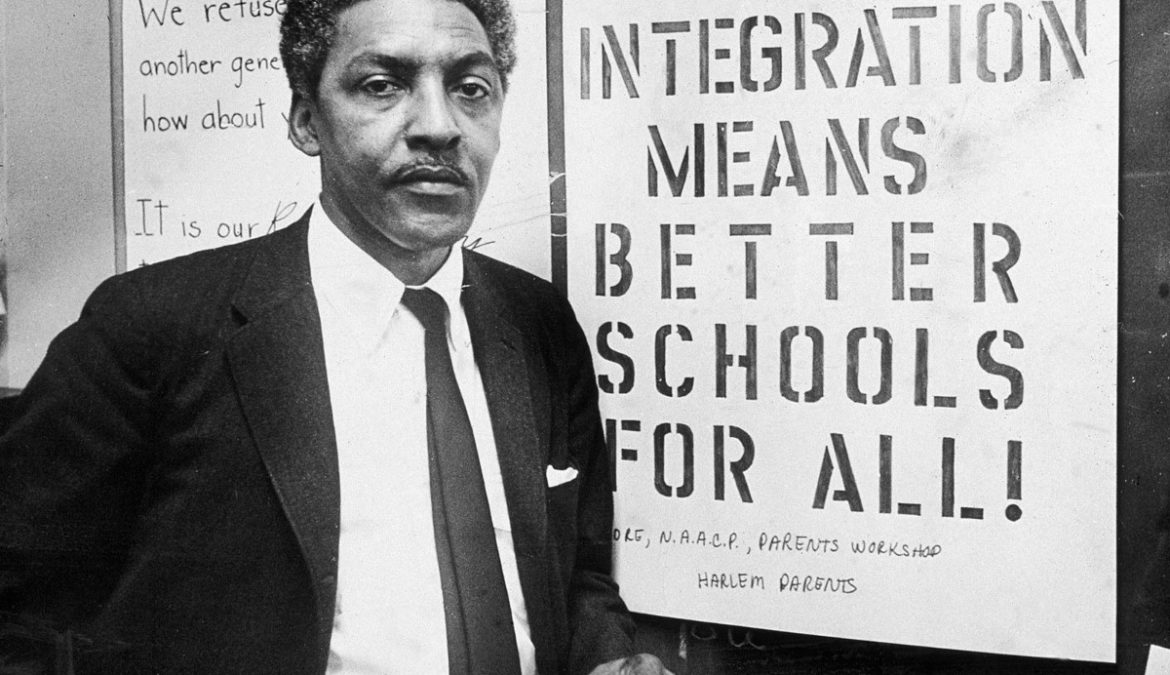

Attorneys from the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People (NAACP), a civil rights organization, appealed the convictions

all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reversed them.

The violence and arrests continued to garner national and

international attention, and drew hundreds of new Freedom Riders to the cause.

The rides continued over the

next several months, and in the fall of 1961, under pressure from the Kennedy

administration, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued regulations

prohibiting segregation in interstate transit terminals. Research more about the

summer of ’61 in the south and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!