GM – FBF – We

who follow the Honorable Elijah Muhammad feel that when you try and pass

integration laws here in America, forcing white people to pretend that they are

accepting black people, what you are doing is making white people act in a

hypocritical way.

Remember – “The Supreme

Court is having a hard time integrating schools. What chance do I have to

integrate audiences?” – Nat King Cole

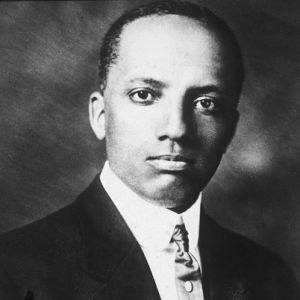

Today in our History – February

6, 1958 – “The Nate King Cole Show” – Season One – Show number 13.

“For 13 months, I was the Jackie Robinson of television”, wrote Nat

King Cole in a revealing 1958 article for Ebony magazine. “After a

trail-blazing year that shattered all the old bug-a-boos about Negroes on TV, I

found myself standing there with the bat on my shoulder. The men who dictate

what Americans see and hear didn’t want to play ball.”

The conventional wisdom about The

Nat King Cole Show is that it was the first network TV program hosted by an

African American, that NBC cancelled it after it failed to attract a sponsor,

and that potential advertisers were reluctant to sign on for fear that their

products would be boycotted by disgruntled Southerners. While based in fact,

none of these statements is exactly true.

At the time of his show’s

premiere, Nat Cole was not merely one of the highest paid black people in

America but one of the most successful entertainers in the world, period. His

gentle, romantic style of singing endeared him to millions, and his record

sales were phenomenal. There was every reason to believe that a TV show

starring Nat King Cole would be a huge hit.

There was just one slight

problem: with legal segregation still in full force in the South and de facto

segregation in much of the rest of the country, TV was, with few exceptions,

the exclusive domain of white people. The rare television images of African

Americans tended to be dumb stereotypes like those seen on Amos ‘n Andy and

Beulah. Even if some in the industry might have been inclined to allow blacks

to present themselves as intelligent and sophisticated, there was no telling

how the audience might react.

Black hosts had been tried

before. Hazel Scott (in 1950) and Billy Daniels (in 1952) had each starred in a

short-lived and quickly forgotten variety show. But Cole’s program was the

first hosted by a star of his magnitude, and expectations were high.

It was obvious that, if Nat were

successful, it would open a lot of doors for other African American

entertainers. There was a whole host of big stars, both black and white, who

wanted to help and were willing to appear on the show for union scale. But

despite the stars and the show’s high entertainment value, decent ratings

failed to materialize.

Had the ratings been higher,

national sponsors might have been willing to support the show. But the combination

of a relatively small audience and skittishness about viewer reaction kept them

away. While crediting NBC with keeping the show on the air, Cole felt

advertisers should have had more guts. “When we went on the air last

summer,” he wrote, “two big companies were on the verge of buying.

But, at the last moment, somebody said, ‘No, we won’t take a chance.’ Two other

sponsors turned us down cold. I won’t call their names, but they were big, very

big. They turned us down and then lost money on inferior shows.”

Carter products, makers of Arrid

deodorant and Rise shaving cream, backed the show for a short time but soon

pulled out. In the absence of a national sponsor, NBC put together a patchwork

of local ones, including Rheingold Beer in New York, Gallo and Thunderbird

Wines in Los Angeles, Regal Beer in New Orleans, and Coca Cola in Houston. But

despite a major push, Cole and NBC just couldn’t dispel the notion among big

advertisers that viewers would object to seeing blacks and whites on an equal

footing and that it would hurt the companies’ sales – despite the fact that

none of the local sponsors had had a problem. “Madison Avenue [is] the

center of the advertising industry,” Cole wrote, “and their big

clients didn’t want their products associated with Negroes…Ad Alley thinks it’s

still a white man’s world.”

It seems silly today, but Cole

had to be careful how he related to his guest stars. In the best show biz

tradition, he liked getting physical with his pals, often putting a friendly

arm around them. But he was mindful never to touch the white women on the show.

It wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that in some parts of the country, even

at that late date, that would have been a lynching offense. Remember, it had

been just two years since the murder of Emmett Till.

That Cole was aware of the

situation is evident in this carefully worded statement: “We proved that a

Negro star could play host to whites, including women, and we proved it in such

good taste that no one was offended…I didn’t bend over backwards, but I didn’t

go out of my way to offend anyone.” (Black women were another story. His

flirting with Eartha Kitt on the October 8, 1957 telecast got so steamy that,

at the close of the show, he felt the need to speak directly to his wife, assuring

her it was all in good fun.)

Despite the controversy behind

the scenes, there was little evidence of it on the show itself. Viewers simply

saw and heard some of the best entertainment television had to offer. Reviewing

the premiere, Variety foresaw “many pleasant quarter-hours to come”

and mentioned “the topgrade quality that’s going into the series.”

The New York Times called the show “a refreshing musical diversion”

with a host possessing “an amiable personality that comes across

engagingly on the television screen.”

While NBC was willing to keep the

show going, Cole decided to call it quits after fourteen months on the air. Two

factors influenced his decision. First, the network wanted to move the show

from Tuesdays at 7:30 to Saturdays at 7:00. Nat felt the move wouldn’t help his

ratings, since in some areas, the program would air at 6:00 or even 5:00. The

other reason was that he didn’t feel comfortable asking his guest stars to work

for practically nothing. “You can wear out your welcome,” he

commented. “People get tired if you never stop begging.”

When the show folded, Cole and

NBC expressed some optimism about reviving it if a national sponsor could be

found, but that never happened. The next African American to try hosting a

program was Sammy Davis Jr. in 1966, but low ratings forced him off the air

after less than four months. It wasn’t until The Flip Wilson Show came along in

1970 that a variety show hosted by a black entertainer became an unqualified

success.

But Nat King Cole was the trail

blazer. “I was the pioneer, the test case, the Negro first,” he

wrote. “I didn’t plan it that way, but it was obvious to anyone with eyes

to see that I was the only Negro on network television with his own show. On my

show rode the hopes and fears and dreams of millions of people.” It was a

dream deferred, but one that eventually came true.

The prejudices

of the era in which Cole lived hindered his potential for even greater stardom.

His talents extended beyond singing and piano playing: he excelled as a relaxed

and humorous stage personality, and he was also a capable actor, evidenced by

his performances in the films Istanbul (1957), China Gate (1957), Night of the

Quarter Moon (1959), and Cat Ballou (1965); he also played himself in The Nat

“King” Cole Musical Story (1955) and portrayed blues legend W.C. Handy in St.

Louis Blues (1958). His daughter Natalie was also a popular singer who achieved

her greatest chart success in 1991 with “Unforgettable,” an electronically

created duet with her late father. Research more about this American and share

with your babies. Make it a champion day!