GM – FBF – Leadership is self-made. People who have deliberately

decided to become problems solver lead better.

Remember – The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands

in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge

and controversy. – MLKJR

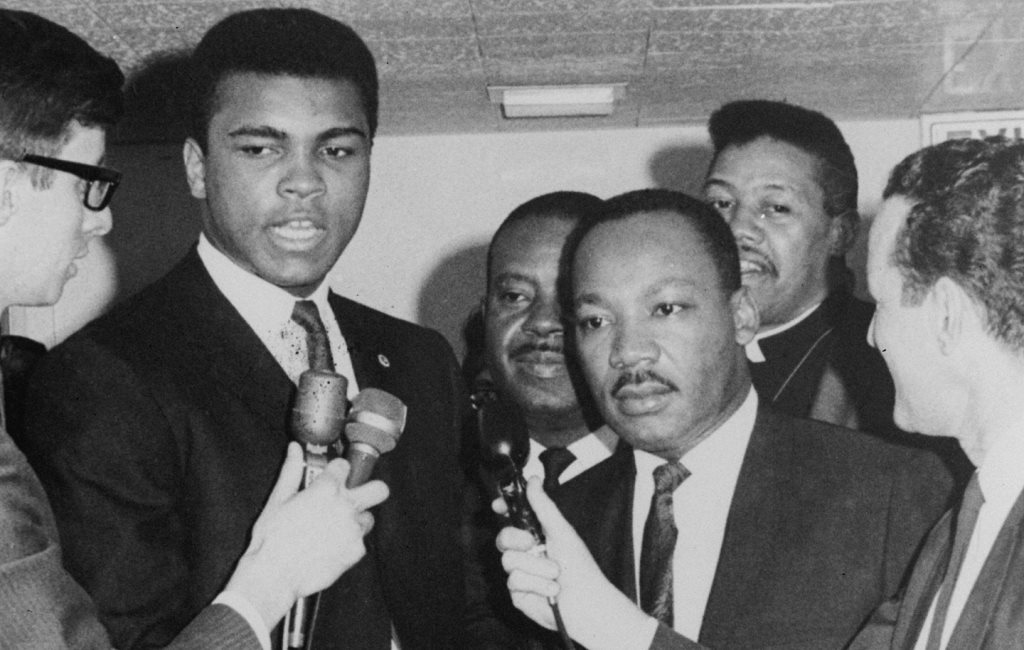

Today in our History – Martin Luther King, Jr. was the

charismatic leader of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Chosen to

lead the Montgomery Bus Boycott at its genesis in 1955, the year-long

nonviolent struggle brought King under the scrutiny of a wary and divided

nation. However, his direction, spokesmanship, and the resultant victory of a

Supreme Court ruling against bus segregation, cast him in a brilliant light.

King then persevered in his quest to obtain civil rights for a

nation of African Americans. He formed the Southern Christian Leadership

Conference (SCLC) to coordinate nonviolent protests and delivered over 2,500

speeches addressing America’s racial injustices, with I Have a Dream being his

most memorable.

When King was assassinated in 1968, the nation shook with the

impact; violence broke out in over 100 cities. To many, Martin Luther King, Jr.

was a hero.

Dates: January 15, 1929 — April 4, 1968

Also known as: Michael Lewis King, Jr. (born as); Reverend

Martin Luther King

Tuesday’s Child

When Martin Luther King, Jr. opened his eyes for the first time Tuesday,

January 15, 1929, he beheld a world that would view him scornfully only because

he was black.

Born to Michael King Sr., a Baptist minister, and Alberta

Williams, a Spelman College graduate and former schoolteacher, King lived in a

nurturing environment with his parents and older sister, Willie Christine, in

the Victorian home of his maternal grandparents.

(A younger brother, Alfred Daniel, would be born 19 months

later.)

Alberta’s parents, Rev. A.D. Williams and wife Jennie, lived in

a prosperous section of Atlanta, Georgia known as “black Wall Street.” Reverend

Williams was pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, a well-established church

within the community.

Martin — named Michael Lewis until he was five — thrived with

his siblings in a secure middle-class family and had a normal, happy

upbringing. Martin enjoyed playing football and baseball, being a paper boy,

and doing odd jobs. He wanted to be a fireman when he grew up.

A Good Name

Martin and his siblings received reading and piano lessons from their mother,

who worked diligently to teach them self-respect.

In his father, King had a bold role model. King Sr. was involved

in the local chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People), and had led a successful campaign for equal wages of white and

black teachers in Atlanta. The elder King was outspoken and fought prejudice

from the pulpit — advocating racial harmony as God’s will.

Martin was also inspired by his maternal grandfather, Rev. A. D.

Williams. Both his father and grandfather taught a “social gospel” — a belief

in personal salvation with the need to apply the teachings of Jesus to life’s

daily problems.

When Rev. A.D. Williams died of a heart attack in 1931,

son-in-law King Sr. became pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he served

for 44 years.

In 1934, King Sr. attended the World Baptist Alliance in Berlin.

When he returned to Atlanta, King Sr. changed his name and the

name of his son from Michael King to Martin Luther King, after the Protestant

reformist.

King Sr. was inspired by Martin Luther’s courage in confronting

institutionalized evil while challenging the formidable Catholic Church.

Attempted Suicide

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s grandmother Jennie, whom he affectionately called

“Mama,” was especially protective of her first grandson. Likewise, King

closely bonded with his grandmother, classifying her as “saintly.”

When Jennie died of a heart attack in May 1941, 12-year-old King

was supposed to be home babysitting 10-year-old A.D. Instead, he was away

watching a parade, disobeying his parents. Inconsolable and racked with guilt,

King jumped from a second-story window of his home, attempting suicide.

He was uninjured, but cried and could not sleep for days

afterward.

King would later talk about the affect his grandmother’s death

had on him. He never forgot his transgression and attributed his religious

development a result of the tragedy.

Church, School, and Thoreau

Skipping both 9th and 12th grades, King was only 15 when he entered Morehouse

College. During this time, King had a moral dilemma — though the son,

grandson, and great-grandson of clergymen, King was uncertain he would follow

in their footsteps. The insular nature of the black, southern, Baptist church

felt unchallenging to King.

Also, King questioned religion’s relevance in addressing the

real problems of his people, such as segregation and poverty. King began

rebelling against a life of service to God — playing pool and drinking beer

his first two years at Morehouse. King’s teachers labeled him an underachiever.

Aimlessly, King studied sociology and considered going into law.

He voraciously read and came upon the essay On Civil Disobedience by Henry

David Thoreau. King was fascinated by noncooperation with an unjust system.

It was Morehouse president Dr. Benjamin Mays, however, who

challenged King to align his ideals with his Christian faith to address social

dysfunction. With Mays’ guidance, King decided that social activism was his

inherent calling and that religion was the best means to that end.

To his father’s joy, Martin Luther King, Jr. was ordained a

minister in February 1948. That same year, King graduated from Morehouse with a

Bachelor of Arts degree in sociology at age 19.

Seminary: Finding A Way

In September 1948, King entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania.

Unlike at Morehouse, King excelled at the predominately-white seminary and was

extremely popular — especially with the ladies. King became involved with a

white cafeteria worker, but was told that an interracial romance would

devastate any career move. King halted the relationship, yet was heartbroken.1

Struggling for a way to help his people, King absorbed the works

of great theologians. He studied Reinhold Neibuhr’s neo-orthodoxy, a concept

which emphasizes human involvement in community and a moral duty to love

others. King studied Georg Wilhelm Hegel’s essentialism and Walter

Rauschenbusch’s social responsibility — which was more consistent with King’s

rationalization of social gospel.

However, King despaired that no philosophy was complete within

itself; thus, the question of how to reconcile a nation and a people in

conflict remained unanswered.

Discovering Gandhi

At Crozer, Martin Luther King, Jr. heard a lecture about India’s leader,

Mahatma Gandhi. As King delved into Gandhi’s teachings, he became captivated by

Gandhi’s concept of satyagraha (love-force) — or passive resistance. Gandhi’s

crusades countered the British’s hatred with peaceful love.

Gandhi, like Thoreau, also believed that men should proudly go

to jail when they disobeyed unjust laws. Gandhi, however, added that one should

never use violence because it only bred hate and more violence. This concept

won India its freedom.

The Christian doctrine of love, King concluded, operating

through the Gandhian method of nonviolence, could be the most powerful weapon

utilized by an oppressed people.

At this juncture, however, King had only an intellectual

appreciation of Gandhi’s method, not realizing that an opportunity to test the

method would soon materialize.

In 1951, King graduated at the top of his class — earning a

Bachelor of Divinity degree and the prestigious J. Lewis Crozer fellowship.

In September of 1951, King enrolled in doctoral studies at

Boston University’s School of Theology.

Coretta, the Good Wife

A most important event occurred outside of King’s classroom and church nucleus.

While still in Boston, King met Coretta Scott, a professional singer studying

voice at the New England Conservatory of Music. Her refinement, good mind, and

ability to communicate on his level enchanted King.

Though impressed by the sophisticated King, Coretta hesitated to

become involved with a minister. She was persuaded, however, when King said she

possessed all the qualities he desired in a wife.

After overcoming resistance from “Daddy” King, who

expected his son to choose a hometown bride, the couple married June 18, 1953.

King’s father performed the ceremony on the lawn of Coretta’s family home in

Marion, Alabama. After their wedding, the couple spent their honeymoon at a

funeral parlor owned by a friend of King (hotel honeymoon suites were not

available for blacks).

They then returned to Boston to complete their degrees, with

Coretta receiving a Bachelor of Music degree in June 1954.

King, an exceptional orator, was invited to preach a trial

sermon at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Their

current pastor, Vernon Johns, was retiring after years of challenging the

traditional status quo.

Dexter Avenue was an established church of educated,

middle-class blacks with a history of civil rights activism. King captivated

the Dexter congregation in January 1954 and in April he agreed to accept

pastorship, following completion of his doctoral thesis.

By the time King turned 25, he had received his PhD from Boston

University, welcomed daughter Yolanda, and delivered his first sermon as

Dexter’s 20th pastor.

Give and Take in Their Marriage

From the beginning, Coretta was committed to her husband’s work, accompanying

him around the world, stating, “What a blessing, to be a co-worker with a man

whose life would have so profound an impact on the world.”2

However, throughout the Kings’ marriage, there was constant

conflict about the role Coretta should play. She wanted to participate more

fully in the movement; while King, thinking of the dangers, wanted her to stay

home and raise their children.

The Kings had four children: Yolanda, MLK III, Dexter, and

Bernice. When King was home, he was a good dad; however, he wasn’t home much.

In 1989, King’s close friend and mentor, Reverend Ralph Abernathy wrote in his

book that he and King spent 25 to 27 days per month away from home. And though

it was no excuse for unfaithfulness, it gave ample opportunity. Abernathy wrote

that King had “a particularly difficult time with temptation.”3

The couple would remain married for nearly 15 years, until

King’s death.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

When 25-year-old King arrived in Montgomery in 1954 to pastor Dexter Avenue

Baptist Church, he didn’t plan on leading a civil rights movement — but

destiny beckoned.4

Rosa Parks, secretary of the local chapter of the NAACP, had

been arrested for her refusal to relinquish her bus seat to a white man.

Parks’ arrest on December 1, 1955, presented the perfect

opportunity to make a strong case for desegregation of the transit system. E.D.

Nixon, former head of the local NAACP chapter, and Rev. Ralph Abernathy

contacted King and other clergymen to plan a citywide bus boycott. The

organizers of the boycott — the NAACP and the Women’s Political Council (WPC)

— met in the basement of King’s church, which he had offered.

The group drafted demands for the bus company. To secure the

demands, no African American would ride the buses on Monday, December 5th.

Leaflets announcing the planned protest were distributed, receiving unexpected

publicity in newspapers and on radio.

Answering the Call

On December 5, 1955, nearly 20,000 black citizens refused bus rides. And

because blacks comprised 90% of the transit system’s passengers, most buses

were empty. Since the one-day boycott was successful, E.D. Nixon held a second

meeting to discuss extending the boycott.

However, the ministers wanted to limit the boycott so as not to

anger the white hierarchy in Montgomery. Frustrated, Nixon threatened to expose

the ministers as cowards. Whether through strength of character or divine will,

King stood to say he was no coward.5

By meeting’s end, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA)

was formed and King was elected president; he had agreed to lead the boycott as

spokesperson. That evening, King addressed hundreds at Holt Street Baptist

Church, stating there was no alternative except to protest.

By the time the bus boycott ended 381 days later, Montgomery’s

transit system and the city’s businesses were nearly bankrupt. On December 20,

1956, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the laws enforcing segregation

on public transit were unconstitutional.

The boycott changed King’s life and the city of Montgomery. The

boycott had illuminated the power of nonviolence to King, more than reading any

book had, and he committed to it as a way of life.

Black Church Power

Buoyed by the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the movement’s leaders met

in January 1957 in Atlanta and formed the Southern Christian Leadership

Conference (SCLC). The group’s aim was to utilize the people-power of the black

church to coordinate nonviolent protests. King was elected president and

remained at the helm until his death.

Several major life events transpired for King in late 1957 and

early 1958 — the birth of a son and the publication of his first book, Stride

Toward Freedom.

While signing books in Harlem, King was stabbed by a mentally

ill black woman. King survived this first assassination attempt and as part of

recovery, took a trip to India’s Gandhi Peace Foundation in February 1959 to

refine his protest strategies.

The Battle for Birmingham

In April 1963, King and the SCLC joined Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth of the Alabama

Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) in a nonviolent campaign to end

segregation and to force businesses to hire blacks in Birmingham, Alabama.

However, powerful firehoses and vicious attack-dogs were

unleashed on the peaceful protestors by “Bull” Connor’s local police. King was

thrown into solitary, where he penned Letter from a Birmingham Jail, an

affirmation of his peaceful philosophy, on April 16, 1963.

Broadcast on national news, images of the brutality wrenched an

unprecedented cry from an outraged nation. Many began to send money in support

of the protesters. White sympathizers joined the demonstration.

In a few days, the protest became so explosive that Birmingham

was willing to negotiate. By the summer of 1963, thousands of public facilities

were integrated across the country and companies began to hire blacks for the

first time.

More importantly, a political climate was created in which

passage of broad civil rights legislation seemed plausible. On June 11, 1963,

President John F. Kennedy proved his commitment to the passage of civil rights

legislation by drafting the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was signed into law

by President Lyndon Johnson after Kennedy’s assassination.

The March on Washington

The events of 1963 culminated in the famous March on Washington in D.C. On

August 28, 1963, nearly 250,000 Americans arrived in sweltering heat. They had

come to hear the speeches of various civil rights activists, but most had come

to hear Martin Luther King, Jr.

Planning the rally had been a group effort, involving King,

James Farmer of CORE, A. Philip Randolph of the Negro American Labor Council,

Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, John Lewis of SNCC, and Dorothy Height of the

National Council of Negro Women. Bayard Rustin, King’s long-time political

advisor, was the coordinator.

The Kennedy Administration, fearing violence would ensue, edited

the content of John Lewis’ speech and invited white organizations to take part.

This involvement caused some extremist blacks to consider the event a

misrepresentation. Malcolm X labeled it the “farce in Washington.”6

The crowd far exceeded the expectations of the event’s

organizers. Speaker after speaker addressed the progress made or lack thereof

in national civil rights. The heat grew oppressive — but then King stood up.

Whether by discomfort or distraction, the start of King’s

oration was atypically lackluster. It is said, however, that King suddenly

stopped reading from penned manuscript, being tapped on the shoulder by renewed

inspiration. Or was it the voice of famed gospel singer Mahalia Jackson

shouting to him “tell ’em about the dream, Martin!”7

Laying jotted notes aside, King spoke from the heart of a

father, declaring that he had not lost hope, because he had a dream – “that one

day my four little children will not be judged by the color of their skin, but

by the content of their character.” The speech King never intended to give was

the greatest speech of his life.

The fact that King’s I Have a Dream speech was comprised of

portions of his sermons and speeches does not denigrate its essence. At a time

when a voice was needed, I Have a Dream so eloquently embodied the soul, the

heart, and the hope of a people.

Man of the Year

Martin Luther King, Jr., now known worldwide, was designated Time magazine’s

1963 “Man of the Year.” In 1964, King won the most coveted Nobel Peace Prize,

donating its $54,123 proceeds to advance civil rights.

But not everyone was thrilled by King’s successes. Since the

Montgomery Bus Boycott, King had been the unknowing subject of the covert

scrutiny of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

Hoover was personally malicious toward King, calling him “most

dangerous.” Hoping to prove King was under communistic influence, Hoover filed

a request with Attorney General Robert Kennedy to put King under constant

surveillance.

In September 1963, Robert Kennedy gave Hoover consent to break

into King and his associates’ homes and offices to install phone taps and

recorders. King’s hotel-stays were subjected to FBI monitoring, which allegedly

produced evidence of sexual activity but none of communist activity.

The Poverty Problem

The summer of 1964 saw King’s nonviolent concept challenged in the north, with

riot outbreaks in black ghettos in several cities. The riots resulted in

massive property damage and loss of life.

The riots’ origins were clear to King — segregation and

poverty. Although Civil Rights had helped blacks, most still lived in extreme

poverty. Without jobs it was impossible to afford decent housing, healthcare,

or even food. Their misery birthed anger, addiction, and subsequent crime.

The riots disturbed King deeply and his focus shifted to the

poverty dilemma, but he was unable to garner support. Nevertheless, King

organized a campaign against poverty in 1966 and moved his family into

Chicago’s black ghetto.

King found, however, that the successful strategies used in the

South did not work in Chicago. Also, King’s impact was diminished by the

increasingly vitriolic rant of the black urban demographic of the period.

Blacks began turning away from the peaceful course of King to the radical

concepts of Malcolm X.

From 1965 to 1967, King met with constant criticism over his

passive nonviolent message. But King refused to discard his firm convictions of

racial harmony through nonviolence. King placidly addressed the harmful

philosophy of the Black Power movement in his last book, Where Do We Go from

Here: Chaos or Community?

To Remain Relevant

Although only 38 years old, Martin Luther King, Jr. had wearied of years of

demonstrations, confrontations, marches, going to jail, and the ever-present

threat of death. He was disheartened by the criticism and the uprising of

militant factions.

Even as his popularity waned, King sought to clarify the link

between poverty and discrimination and to address America’s increased

involvement in Vietnam. In a public address, Beyond Vietnam on April 4, 1967,

King stated that the Vietnam War was politically unjustifiable and discriminatory

towards the poor. This placed King under the watchful eye of the FBI even more.

King’s last campaign seemed a precursor to today’s “occupy”

movement. Organizing with other civil rights groups, King’s Poor People’s

Campaign would bring impoverished people of various ethnicities to live in tent

camps on the National Mall. The event would take place in April.

Martin Luther King’s Last Days

In the spring of 1968, drawn by a labor strike of black sanitation workers,

King went to Memphis, Tennessee. King joined the march for job safety, higher

wages, union recognition, and benefits. But after the march began, a riot broke

out — 60 people were injured, one killed. This ended the march and a saddened

King went home.

Upon reflection, King felt he was surrendering to violence and

returned to Memphis. On April 3, 1968, King gave what proved his last speech.

Towards the end, he stated that he wanted a long life but had been warned he

would be killed in Memphis. King said that death did not matter now because he’d

“been to the mountaintop” and had seen “the promised land.”

On the afternoon of April 4, 1968 — a year to the date of

delivering his Beyond Vietnam argument, King stepped onto the balcony of the

Lorraine Motel in Memphis. A rifle blast rang out from a boarding house across

the way. The bullet tore into King’s face, slamming him against a wall and onto

the ground. King died at St. Joseph’s Hospital less than an hour later.

Free at Last

King’s death brought tremendous grief to a violence-weary nation and race riots

exploded all over the country.

King’s body was brought home to Atlanta so that he could

lay-in-state at Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he had co-pastored with his

father for many years.

On Tuesday, April 9, 1968, King’s funeral was attended by dignitaries

and commoners alike. Great words were spoken to eulogize the slain leader.

However, the most apropos eulogy was delivered by King himself, when a tape

recording of his last sermon at Ebenezer was played:

“If any of you are around when I meet my day, I don’t want

a long funeral… I’d like someone to mention that day that Martin Luther King,

Jr. tried to give his life serving others… And I want you to say that I tried

to love and serve humanity.”

King’s body is interred at the King Center in Atlanta, Georgia.

Martin Luther King’s Legacy

Without question, Martin Luther King, Jr. achieved much in the short span of

eleven years. With his accumulated travel of over six million miles, King could

have gone to the moon and back four-and-a-half times. Instead, he traveled the

world giving over 2,500 speeches, writing five books, participating in eight

major nonviolent recourses to effect social change, and was arrested over 20

times.

In November 1983, President

Ronald Reagan honored Martin Luther King, Jr. by creating a national holiday to

celebrate the man who did so much for the United States. (King is the only

African American and non-president to have a national holiday.) Make it a

champion day!