GM – FBF – This is last entry for the year 2018 and I have a

different story for every day of this year. I want to thank all of you who have

stopped by and gotten something from the daily posts and for the ones who went

on to share the daily posts.

One hundred years ago 1919 was called “The Red Summer” with all

of the lynching’s that Black people faced. I will tell many of those stories in

2019.

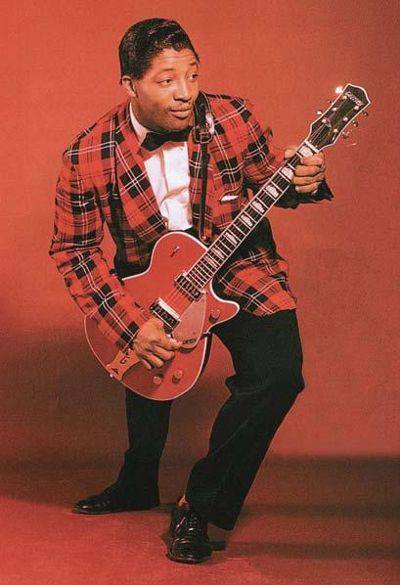

Today’s Story is about a Black athlete who broke the color

barrier in professional football in 1946 (a year before Jackie Robinson

integrated major league baseball) and is regarded as having the first dignified

role for a black actor in a feature motion picture. Enjoy!

Remember – “ I have been able to serve my country, play

professional football and do acting in Hollywood. I have a good life” – Woodrow

Wilson Stride

Today in our History – December 31, 1994 – Woodrow Wilson

Woolwine (Woody) Strode dies.

(B. 28 July 1914 in Los Angeles, California; d. 31 December 1994

in Glendora, California), Strode was one of two sons of Baylous Strode, Sr., a

brick mason, and Rose Norris Strode, a homemaker; Baylous Jr. was the couple’s

only other child.

Strode was tall and thin as a youngster, and his athletic

ability did not materialize until he reached junior high school. After a growth

spurt, he developed into a fine all-around athlete, earning all-city honors in

football and all-state recognition in track and field at Thomas Jefferson High

School in Los Angeles. His athletic ability interested several major colleges

on the West Coast. He chose the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA),

at the time a relatively young institution that had recently moved to a new

campus in the Westwood section of Los Angeles. In going to college, Strode

fulfilled his father’s wish that he “get an education.”

During the late 1930s Jackie Robinson and Kenny Washington, also

black athletes, were the bright stars on the UCLA gridiron, but Strode was also

outstanding. It was at this time that Strode prepared for the decathlon (a

ten-event track and field sport) in the 1936 Olympic trials.

Because of his muscular physique, Strode was asked to pose for

an art class. He also caught the attention of the acclaimed German

cinematographer Leni Riefenstahl, who took several still photographs of Strode

and had him pose for a sculptor. The Nazi leader Adolf Hitler saw the

photographs and sent Riefenstahl to America to film Strode. A painting of

Strode was used, ironically—given Hitler’s thoughts on Aryan supremacy—as part

of the Berlin Olympic Festival in 1936.

When Strode finished his schooling at UCLA, the National

Football League (NFL) was still an all-white organization. Blacks had no

opportunity to play in the nation’s only major professional football league.

However, Strode and Washington did play with the Hollywood Bears of the Pacific

Coast League, a minor league, and they actually earned more money than many NFL

players.

During the late 1930s Strode and his UCLA teammate Washington

began working in the service department at Warner Brothers Studio. After he

left UCLA, Strode’s contacts at Warner Brothers allowed him to secure small

roles in motion pictures, including Sundown (1941), Star-Spangled Rhythm(1942),

and No Time for Lave (1943). But Strode was mainly an athlete during this time.

When not playing football, he trained as a wrestler and won several

professional matches. In 1941 he married Luana Kalaeloa, a Hawaiian princess.

They later had two children: a son, Kalaeloa (known as Kalai), and a daughter,

June.

When World War II broke out, Strode joined the U.S. Army Air

Corps. He was stationed at March Field in Riverside, California, where he was a

member of one of the top service football teams, the Fourth Air Corps Flyers.

Commenting on Strode, Paul Stenn (“Stenko”), a ten-year NFL player, recalled,

“I played along side of him—and he was good. I had played pro football and I

can tell you Woody Strode was as good as the NFL players. He just needed a

chance to prove it.”

Strode got that chance after the war. When the Cleveland Rams

moved their franchise to Los Angeles in 1946, they became the first major

league team to play on the West Coast. The Rams wanted to play in Memorial

Coliseum, a 100,000-seat stadium. Leaders of the black community reasoned that

if the team was going to play in a public facility, then all Americans should

be entitled to play on the team. Pressure was brought to bear, and in the

spring of 1946 Strode and Washington signed on with the Rams, becoming the

first blacks to play in the NFL since the league’s pioneering days in the

1920s. Unfortunately, both Strode, then age thirty-two, and Washington, then

twenty-nine, were past their athletic prime. Underutilized by the Rams, Strode

caught only four passes for thirty-seven yards and was waived at the end of the

1946 season.

The next season, Strode signed with the Calgary Stampeders of

the Canadian Football League. Age and football injuries caught up with him by

1950, and Strode returned to the United States to pursue a professional

wrestling career in Los Angeles. The “movie crowd” often attended the wrestling

matches, and this led to Strode’s full-time acting career.

A talent agent signed him, and he appeared in several movies

that today would be known as “action” films. Strode often played the role of a

gladiator or jungle warrior. He gained notoriety as a gladiator in the 1960

epic film Spartacus. That same year Strode starred in the title role of

Sergeant Rutledge, a part that many consider to be the first dignified black

character in American cinema. Strode continued to land meaningful roles

throughout the 1960s and made films in Italy in the 1970s. He also made regular

television appearances, ranging from a starring role in Ramar of the Jungle to

a part in The Quest.

One of Strode’s last major roles was in the 1984 film The Cotton

Club. After he did several other feature films and a television movie (A

Gathering of Old Men, 1987), Strode retired to a ranch in Glendora, California,

with his second wife, Tina (Strode remarried on 10 May 1982 after Luana’s death

in 1980 from Parkinson’s disease). Strode died on New Year’s Eve, 1994, in

Glendora of natural causes about a year after he was diagnosed with lung

cancer. He was buried with full military honors in Riverside National Cemetery

in California.

Strode was a versatile

athlete who made his mark in the world of sports, but he is best remembered as

one of the first blacks to integrate the modern NFL. He also left an important

legacy of more than fifty feature films. His many significant roles opened the

door for other black actors to follow—much like his role as a black pioneer in

professional football led the way for future black athletes. Research more

about Black athletes turning to movie stars and share with your babies. Make it

a champion day!