GM- FBF – Our story today is a prelude to what is happening and

will intensify more in the summer of 1919. The “bloody summer” as it will be

called in many urban areas of the United States, As WWI draws to a close in

America compared to the black troops in France are getting a different

experience. Today’s story will be no different than East . Louis, IL. and other

cities. Enjoy!

Remember – “They told us to put on the Uniform and we can show

are support to this Country for the war effort, it was a lie for many of us” –

Unknown Black soldier

Today in our History – On Dec. 11, 1917, 13 black soldiers were

hanged for their part in a little-remembered and deadly race riot. They were

condemned to death after a trial many called unjust.

Now, at a moment when the continuing impact of racism in

policing and criminal justice is a topic of fraught public conversation

throughout the United States, relatives on both sides of that Houston riot are

uniting to preserve the memory of the event and to find some justice for those

executed soldiers.

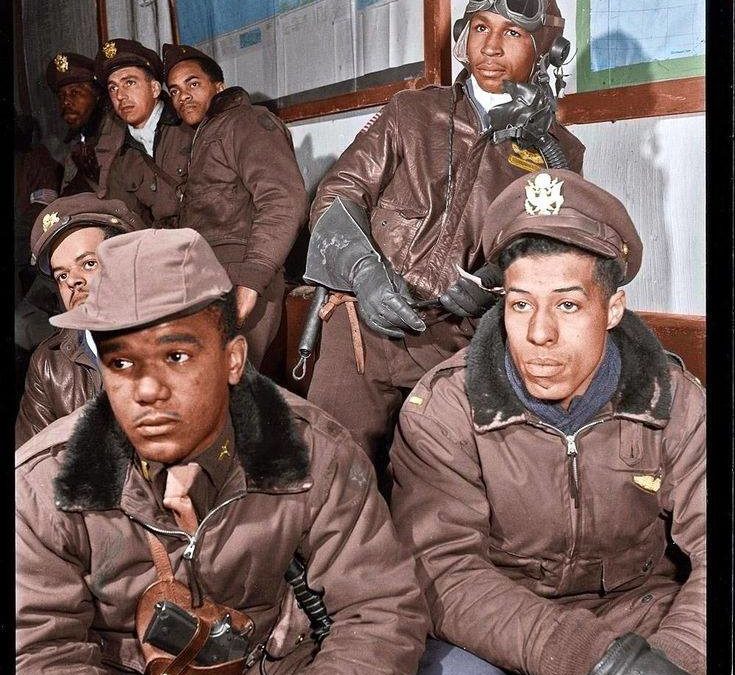

It began in July 1917, following America declaring war on

Germany and entering World War I. The 3rd Battalion of the 24th United States

Infantry, a predominantly black unit, was sent to guard the construction of

Camp Logan — part of the new war effort — on the edge of Houston.

From the beginning, the soldiers encountered Jim Crow law and

racism from police and civilians; workers constructing the camp resented their

presence.

“They sent these soldiers into the most hostile environment

imaginable,” says Charles Anderson, a relative of Sgt. William Nesbit, one of

the hanged soldiers. “The soldiers should never have been sent there — they

should have remained at their base in New Mexico until the order came to go to

France.”

Tensions mounted until around noon on Aug. 23, when the Houston police arrested

a black soldier for allegedly interfering in the arrest of a black woman,

triggering a rapid escalation of events leading to false rumors reaching Camp

Logan by evening that a soldier had been killed and that a white mob was

approaching the camp.

Soldiers grabbed rifles and headed into downtown Houston,

against the orders of their superior officers. The rampage lasted two hours and

involved gun battles between the soldiers and the police and local residents,

with bayonets being used, leaving 16 white locals dead, including five

policemen. Four black soldiers also died.

After tempers finally cooled, the soldiers returned to camp. The

next day martial law was declared in Houston, and the following day the unit

was dispatched back to New Mexico before three courts-martial were convened to

try 118 indicted soldiers.

Sixty-four men were tried in San Antonio, charged with

disobeying orders, mutiny, murder and aggravated assault, during the first court-martial

that began Nov. 1 — the largest murder trial in US military history —resulting

in the 13 death sentences.

“They were represented by just one lawyer and didn’t even have a

chance to appeal,” says Angela Holder, great-niece of Cpl. Jesse Moore, one of

the hanged soldiers, and a history professor at Houston Community College.

“They were denied due process guaranteed by the Constitution.”

Not one Houstonian among the prosecution witnesses could

identify a soldier as having fired shots that killed someone, while routinely

referring to the accused using the n-word. Seven soldiers agreed to testify

against the others in exchange for clemency.

On Nov. 28, the 13 men were found guilty and sentenced to death.

Two weeks later, without an appeal, they were hanged on Dec. 11.

Shortly after the hasty executions, and in the face of

condemnation from both military and civilian figures, the US Army made changes

to its Uniform Code of Military Justice to prevent executions without a

meaningful appeal. These changes remain in place to this day.

It was too late for the soldiers hanged from a scaffold beside

the Salado Creek in San Antonio. But some in Houston say it’s not too late for

some kind of justice. During the Obama presidency, soldiers’ relatives lobbied

— unsuccessfully — for posthumous pardons. The petitions have now been sent to

the Trump White House.

Holder was more successful in 2017 at lobbying the Veterans

Association for gravestones in a Houston cemetery for two soldiers killed

during the riot. And along with other local activists, she also helped organize

the Aug. 23 rededication of a Texas Historical Commission marker at the former

site of Camp Logan to mark the riot’s 100th anniversary.

The ceremony was attended by Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner, who

said the history of the event is “calling us today to be better,” and “for good

people of all backgrounds to speak against hate and stand united.”

And it wasn’t the only 100th anniversary to help focus the minds

of those familiar with the riot on the past, present and future.

“The centennial of the US entry into World War I has likely

brought a heightened awareness of such events and emboldened people to address

a sensitive topic,” says Lila Rakoczy, program coordinator of military sites

and oral history programs at the Texas Historical Commission.

Also, recent national police controversies have struck

unfortunate parallels with events surrounding the riot.

“This was a problem created by community policing in a hostile environment,”

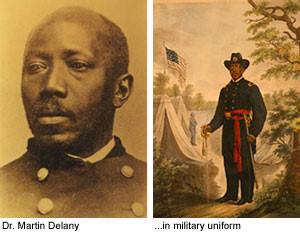

says Paul Matthews, founder of Houston’s Buffalo Soldiers National Museum,

which examines the role of African American soldiers during US military

history. “The soldiers were standing up for America when it wasn’t standing up

for them.”

A similar perspective is shared by some relatives of those who

suffered because of the rioting soldiers.

“The soldiers were 100 percent wrong for rioting, but I don’t blame them,” says

Jules James, great-nephew of Capt. Bartlett James, one of the battalion’s white

officers who managed to restrain a larger number of soldiers from leaving camp

but died under mysterious circumstances before the court-martial, notes James,

who has researched the history. “The unit had 60 years of excellent

service, was full of experienced veterans but couldn’t endure seven weeks of

Houston.”

Current attempts to deal with this racial tragedy brought Sandra

Hajtman, great-granddaughter of one of the policemen killed, together with

Holder and Anderson when they met to retrace the Houston streets taken by the

rioting soldiers.

“The men did not have a fair trial,” Hajtman says. “I have no doubt about the

likelihood the men executed had nothing to do with the deaths. You have to look

at the whole story, why it happened, and learn from it — both sides bear

responsibility.”

Relatives continue waiting for a response to the pardon

petitions. In the meantime, preserving the memory of the Houston riot and its

aftermath has itself served as a kind of justice for the relatives of the

soldiers and police who died because of it.

‘’Sandra Hajtman’s ancestor, who was killed, was a good

policeman and would bring abandoned black children to his home where his wife

would nurse them,” Anderson says. “No one should have lost their life that

night had the right decisions been made. It was a very sad tragedy that did not

need to happen.”

In November, the largest court-martial in U.S. military history

convened at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio to try sixty-three soldiers from

the Third Battalion. Thirteen of the convicted men were executed by hanging on

December 11.

The following year, two additional courts-martial were held and

another sixteen sentenced to hang. Responding to pressure from black leaders,

President Woodrow Wilson commuted the death sentences of ten of the condemned

men. In total, nearly sixty soldiers received life imprisonment for their roles

in the affair. The Houston Mutiny anticipated the “Red Summer” riots of 1919 in

which many African American servicemen retaliated against white mistreatment.

On the other hand because of the Mutiny, the Twenty-fourth Infantry Regiment

was not allowed by the U.S War Department to go to France to fight in World War

I.

Houston marked an anniversary

in December that some in the city would perhaps rather forget — and others

demand be recalled more clearly. Research more about this and other events

leading up to the “Red Summer” and share with your babies. Make it a champion

day!